In an 1851 letter, Daniel’s brother Kenneth describes him physically as the smallest one of the “tribe,” perhaps one reason he was inclined toward pursuits that required some education. Duncan McKenzie would also describe Daniel as “reserved” in nature.

After his experience in the Mexican War, he may have become more cautious. He hesitates for some years before practicing medicine because he is weighing the risks of having to make a life or death decision. His lack of formal education in this profession undoubtedly gave him pause.

By the time Daniel C. McKenzie’s parents, Duncan and Barbara (McLaurin) McKenzie arrived in Covington County, MS in 1833, they had already provided their older children with educational opportunities better than many. Barbara’s brother, Duncan McLaurin, was a respected educator in Richmond County. His own school records show that he taught the oldest children of Duncan McKenzie and the children of Duncan’s brother, John. Daniel’s Uncle Duncan was an inspiring teacher for many of his students, evidenced by the number who corresponded with him as adults even from distant places. Of the six McKenzie brothers, Daniel was most inspired to further his education.

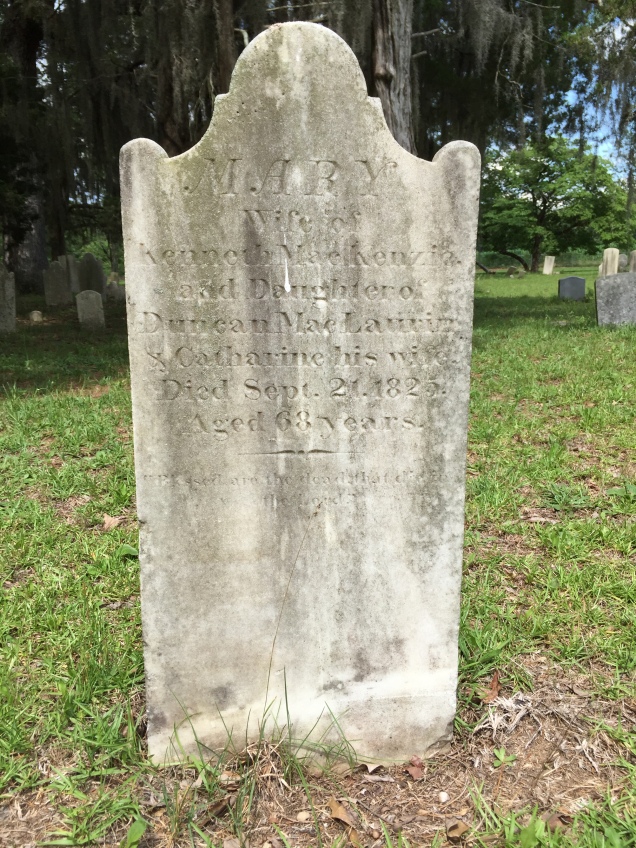

Daniel was born on 9 August 1823 when his parents were both about thirty years old and farming on property in Richmond County, NC. Daniel’s McLaurin grandparents, a number of unmarried aunts, and Uncles Duncan and John McLaurin were living within visiting distance at Gum Swamp. His grandfather, Hugh McLaurin, had named his new residence Ballachulish after the home in Scotland he had left in 1790. Until about 1832, paternal grandparents Kenneth McKenzie and Mary (McLaurin) McKenzie also lived near. Mary died in 1825. Kenneth would leave Richmond County around six years later. Duncan McKenzie, likely responding to the siren call of abundant land and cotton wealth, would follow a number of relatives and friends, who were successfully making money farming in Mississippi. Daniel was probably about ten when the family arrived in Covington County, MS near Williamsburg.

Farming would occupy everyone living on the place. For some time the farm land in North Carolina had become increasingly overworked, and a farmer with five sons would be desirous of establishing an inheritance for them. The prospect of making a fortune growing cotton on fertile land newly opened by Native American removal is what likely drew them to migrate. However, Duncan McKenzie admits after about a decade that any success is hard won. The family probably remained of the yeoman class. The vicissitudes of economic trends, the currency and banking problems that plagued the nation, challenged the family. What ultimately concerns Duncan about having migrated is the diminished prospect of educating his children. Duncan, as most Mississippi small farm families, would depend upon locally operated tuition schools. Teachers did not often remain in one place for very long. He laments in his letters to his brother-in-law that, though he is satisfied with his move, a satisfactory formal education for his children is elusive. Daniel in particular is most desirous of an education and has benefited from an early emphasis on such in the place of his birth.

In an 1838 letter Duncan McKenzie considers sending Daniel, and perhaps his younger brother Duncan, back to North Carolina for schooling. The departure of a mutual friend, Gilchrist, for a visit to North Carolina has tempted Duncan to send them with this responsible person:

I am almost tempted to send Danl with

Gilchrist to your school, his youth will for the present

Save him the ride, Should you continue teaching for any

length of time equal to that which would be necessary

for the complition of his education, let me know the cost

of board books & tuition anually in your next, I may

Send him or per haps both Danl & Dunk, it is not

an easy matter to educate them here — Duncan McKenzie

Of course, Daniel never makes the trip to North Carolina for his education. In the end it is too expensive, and every person is needed on the farm.

A year later, Duncan is somewhat appeased when the community near Williamsburg is able to persuade a Mr. Strong of Clinton Academy to conduct a school near them in which Latin will be taught. Duncan even finds Daniel a pony to ride the four miles it will take to get him back and forth from school:

Danl has once more commenced the studdy of Lattin under

the instruction of a Mr Strong late principal of the

clinton Academy Hinds Co. Mr Joshua White and others

of the neighborhood Succeeded in getting a School for

Strong in 4 miles of me I procurd a pony for Danl

to ride, he is in class with Lachlin youngest Sone of

Danl McLaurin of your acquaintance of yore and Brother to Dr Hugh Fayetteville —

Danl tho 3 years from that studdy appears to have retained

it tollerable well — Malcolm Carmichael, Squire

Johns sone has a small School near my house Dunk

Allan and Johny are going to him, he Malcolm came

here early in Janry and took a Small school worth

Say $20 per month — Duncan C. McKenzie

Duncan ends this March 1838 letter by describing Daniel’s hurry to be off to school. On the way to school, he will be mailing the letter Duncan has just finished at the designated Post Office in Williamsburg.

By 1839, Daniel’s father is present at a school examination and was not pleased with the progress of the students, though Daniel and a friend, James L. Shannon, appear to have been the best in the class, according to his father. He tells Duncan McLaurin that if he had them for a year, he “would not be ashamed of them.” By 1841 Daniel is crushed when his friend and classmate James Shannon leaves to attend St. Mary’s Catholic College in Kentucky. Earlier another classmate, Lachlan McLaurin, had also quit the local school. Despite the loss of his companions to other pursuits, Daniel appears to have maintained his desire for an education.

Daniel likely joins in with his brothers hunting in the forests near their home and engaging in what they call “swamp drives,” attempts to flush out a wild boar. In 1839 Duncan reports that Daniel had an accident pricking his foot on a rusty nail. In the 19th century this would be the cause for some concern, because the chance of infection was great with no antibiotics available. Evidently, the wound was kept clean so that infection was avoided.

At his uncle’s request in July of 1843, Daniel composes his first letter to former teacher Uncle Duncan McLaurin at Laurel Hill, NC. Daniel would have been about twenty years old when writing, with some justifiable pride, about his first teaching position. Clearly, the language of the letter is carefully constructed to impress upon his uncle that he has been a worthy recipient of Duncan’s early tutelage. His use of literary allusion, Latin phrase, and political reference reveals an intimate knowledge of his audience. Perhaps Duncan McKenzie, long time correspondent with Duncan McLaurin, hovers nearby offering suggestions to his son as to content. Daniel authors only five letters that survive in the Duncan McLaurin Papers, but each one attests to historical events and personal landmarks in his own lifetime.

He begins this first letter by admitting that his father has told all of the interesting news already, “which renders one almost barefoot in commencing.” However, he commences by describing his teaching position. It is a small school about seven miles from their home in Covington, County. He teaches about twenty five students at one dollar and fifty cents per month. The tuition is two dollars and fifty cents for teaching Latin. Daniel is boarding with a Revolutionary War veteran, John Baskin. Baskin, “comfortably wealthy,” lives with an aging daughter and orphaned grandson. Baskin’s library includes books that are meant to improve the mind of the young, and Baskin’s storytelling pleases Daniel very much. He relishes the quiet as well — likely the kind of peace after a long day only a teacher could appreciate. Daniel describes Baskin’s stories as “history to me they are interesting and entertaining he considers an hour occasionally is not ill spent when devoted to Politics.” I can imagine Duncan McLaurin settling in to read this letter with earnest at the mention of politics. Daniel explains that Baskin’s opinion rests somewhere between that of John C. Calhoun and Thomas Jefferson. Daniel explains with literary allusion:

he is cherished

in principle like Paul at the feet of Gamaliel between

the contrasted feet of Calhoun & Jefferson this stripe

in his political garment he says is truly Republican

but in reality it seems to me to be of rather a different

cast more like the gown of the old woman Otway

if you will allow me to make such

comparisons — Daniel C. McKenzie

Gamaliel was a Jewish teacher and Christian Saint, a person admired by both Christians and Jews. The “old woman Otway” is a dramatic character created by the 17th century English dramatist Thomas Otway. Otway casts a beautiful woman as a catalyst for war. Apparently, during the nineteenth century the plays of Thomas Otway were receiving somewhat of a revival.

Daniel continues in this first letter to express a desire for further education but says he will be patient since he is of an age now that he must be getting on with his adult life. In a political vein, he also mentions that his employers are preparing a barbecue at or near the schoolhouse, “intending to celebrate the day hard as the times are.” This barbecue is held in conjunction also with an election for a representative, “to attend the call session of the legislature.” He ends this letter offering his best to his grandfather, Hugh McLaurin of “Ballachulish”.

In October of 1843 Duncan McKenzie writes of Daniel’s devotion to his students. Apparently, Daniel has been grieved by the death of two of his young charges, the funeral of one from which he has just returned. In the coming years Daniel would teach in Laurence County. By 1845 Daniel would encourage his brother Kenneth to teach as well, though Kenneth’s attempt to do this work does not last very long. Daniel would teach in Garlandsville in Jasper County, where he enjoyed, “the rise if 30 scholars his rates are $1 1/2 to 3 per month.” In Garlandsville he is boarding with a Dr. Watkins, whose library he uses to study medicine. Apparently, Dr. Watkins is a physician of some respect in the community. Unfortunately, the school becomes overcrowded. Likely, a study regime in addition to teaching a large school was a challenge. His father describes him as having lost some weight by the time he returns from Garlandsville.

Whether Daniel will follow teaching as his life’s career is still an open question to his father. Daniel evidently is still yearning for more schooling, likely towards becoming a physician. His father writes in 1845 regarding his difficulty in reading Daniel’s intentions:

Danl has not at any time reveald to me directly his intentions in

regard to his future plans or intentions in fact it is a matter of common

remark that he is distant and reservd and very difficult to become

acquainted with I think he seldom tells anyone what he intends

doing until he is engaged in it — Duncan McKenzie

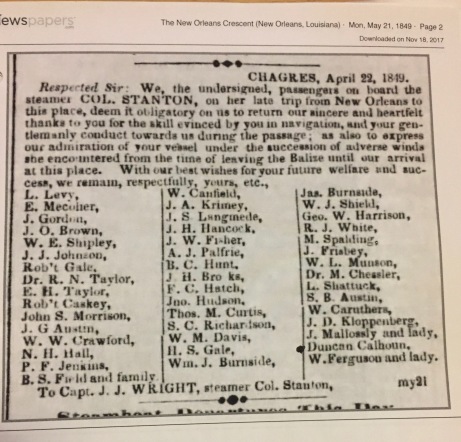

While Daniel is fighting in a Vera Cruz skirmish during the Mexican War, his own father is at home dying. Daniel’s next letter to his uncle is written after his return from serving briefly as a volunteer in the war with the “Covington County Boys” and after his father’s death. Daniel opens his August 1847 letter by saying that he had been home more than a week. Daniel had been one of eight Covington County men, who voluntarily served as amateurs in the war with Mexico. They were “enrolled in Captain Davis’s company, Georgia Regiment, under Gen. Quitman,” according to the article, “From Tampico and the Island of Lobos,” published in The Weekly Mississippian from Jackson, 19 March 1847.

Daniel explains that the group was sent home after one of them, Thomas H. Lott, died after a skirmish at Vera Cruz. The injury to his thigh was not lethal until it became infected — the only casualty of the eight. Many soldiers in this war died of diseases such as malaria, typhoid fever, or dysentery. Another of the group, Cornelius McLaurin, was very ill during the skirmish at Vera Cruz. Indeed, all of the group were ill of dysentery at one point or another. Their return was expedited after Daniel receives news of his father’s death and the general ill health of families in Covington County. Upon return he found their health improving:

I was at the gate before I was recognized, tho

at midday — They had heard here that we had gone to

ward Jalapa (Xalapa), a town in the interior, by way of Cerra Gordon (Sierra Gorda)

and of course was not expecting me. — Daniel C. McKenzie

While in Mexico, Daniel is impressed enough with the Castle San Juan de Cellos to attempt a description in his letter. Situated over a half mile into the sea, large ships are able to anchor very near the walls. Daniel illustrates in the following words:

This castle, worthy of the

name too, covers ten acres of ground on water the wall in

the highest place is seventy feet being eight feet through at

the top and thirty where the sea water comes up to it. I should

judge forty feet through at the base The wall is built of coral

stone the light house out of the same is as much larger

than the one at the Balize [La Balize, LA] of the Miss River, which is a

large one, as the latter is larger than a camson brick

chimney on the walls of this castle were … 300 heavy

pieces of cannon which were kept warm from the morning

of the 10th to the 27th March tho they did but little damage — Daniel C. McKenzie

Daniel admonishes his uncle to tell Uncle John McLaurin that he had purchased a new gun in New Orleans. His brother Kenneth refers to this gun as “Daniels Spaniard gun.” Daniel says that he paid forty-five dollars for the gun, “which will hold up — 300 yards I shot Mexicans at 100 yards distance with it — I will put it to better use and kill birds and squirrels.”

Two references in Daniel’s letter are indicative of racial attitudes at the time. He refers to his Mexican enemies as “the tawny creatures.” Toward the end of his letter he complains, I think in a lighthearted manner, that his ink is pale and a “rascally nigger youngun rumpled the paper about the time I was finishing.” Although this last comment was perhaps even affectionately made, it was based in the general belief of the superiority of the white race. The child to whom Daniel refers was the very young daughter of one of the female enslaved persons on the farm. According to her husband Duncan McKenzie, Barbara had developed a special relationship to this female child. Both of Barbara’s daughters had died, probably leaving her quite open to having a close relationship with a female child. Part of Barbara’s daily task on the farm was to have charge of the enslaved children too young to work. Today we understand from the science of the human genome that differences among the people of the earth have little to do with skin color. The differences we have from one another cannot scientifically be used to indicate racial superiority. However, Daniel, his mother, and her favored enslaved child were living in a 19th century world.

Daniel is farming with the family but admits that he has, “taken up my medical books again.” These two pursuits occupy Daniel’s time. He knows he is needed on the farm now more than before his father’s death and reassures his uncle that their crops will likely sustain them this season. One battlefield experience for Daniel was apparently enough. He considers returning to fight in the military but quickly decides his absence in a war would increase his mother’s grief. After his Mexican War experience, Daniel would commit himself to farming, teaching, and studying to be a physician, a lifelong dream.

As far as becoming a practicing physician, Daniel admits to some hesitancy. In his letter of November 1851, he has apparently been considering it seriously. Traveling in Mississippi has occupied much of his time. Since October he has traveled over, “some dozen counties or more in the upper part of the state.” Franklin County, Mississippi near Natchez was another destination. While there he stopped to visit John Patrick Stewart, son of Allan Stewart and a friend of his uncle’s. Daniel, decades younger than Stewart, describes him as “again elected clerk in that County (Franklin) I was in Meadville and found the contented old Bachelor with fiddle in hand trying to learn to play some sacred songs on that instrument.” In addition, Daniel discovers that Dr. Lachlin McLaurin has enjoyed a successful medical practice in Franklin county. In the end, Daniel tells his uncle, “I prefer school teaching for a little to jeopardizing the lives of fellow creatures for mere money.” Evidently, he still lacks the confidence that a formal education and licensing program may have given him. Mississippi had declared its attempt at medical licensing requirements unconstitutional some years earlier. However, many physicians left the state for a medical education. One such person, and likely a distant relative of Daniel’s, was Dr. Hugh C. McLaurin of Brandon, MS. Hugh would have been a bit older than Daniel, but his family had the means to send him to Pennsylvania to study medicine. According to Duncan McKenzie, in 1846 while teaching school Daniel reads from some of Hugh’s medical books. (Hugh is of the B family of McLaurins and Daniel from the F family. Ancestors of these two family lines came to America in 1790 aboard the same ship. A number of descendants migrated to Mississippi from the Carolinas.)

In the 1850 census Daniel is listed as living with his mother, who is head of household. He is twenty-seven when he travels over parts of the state considering his future. Between his travels he manages to be at home in order to vote in the elections. Duncan McKenzie had been a southern Whig and his sons at first follow in that political tradition. Daniel and his brothers at this point are Unionists and do not want to see the Democrats, or Locofocos, as they are called, control state politics. It appears that in early 1850s Mississippi at least the idea of breaking up the Union over slavery remains a partisan issue. Daniel writes,

The political contest in Mississippi is over

and though the waves still run high the storm

has moderated to a gentle breeze. Foot has gained

the day by a few feet about 1500 votes as I hear …

Brown in this the 9th district has succeeded in beating

our Union Candidate Dawson by a considerable

majority In this part of the state the people

are so tied up in the fetters of Locofocoism

that nothing is too dear to sacrifice for its

promotion. — Daniel C. McKenzie

The “Foot” he references is Henry S. Foote, Whig candidate and winner of the election for governor of Mississippi in 1851. He explains that Democrat former Governor Albert Gallatin Brown’s hue and cry was that keeping the Union in tact was a “Whig trick.” Daniel knows that his Uncle Duncan would be interested in the political success of another relative: “John R. McLaurin son of Neill of Lauderdale County who prides himself in being called a, descendant, of Glen Appin is elected to the Legislature from that county Disunion of course.” John R. McLaurin is Daniel’s second great Aunt Catherine of Glasgow’s grandson from the D family of McLaurins.

In this letter, Daniel mentions a McKenzie relative, his Uncle John McKenzie’s son, who has apparently been overcome with religious zeal to the point that he has been declared insane. This begs the question at what point religious enthusiasm crosses that fine line from fervent piety to mania. Daniel writes his opinion on the matter: “though the cause which he advocates is much assuredly the one and only thing needful yet certainly so much zeal as to destroy that better part which he wished to save and which survives the grave was not at all necessary.” He expresses hope that time will restore his cousin’s reason.

Daniel ends his 1851 letter saying that the talk of Covington County is “money and marrying” and starting for Texas.

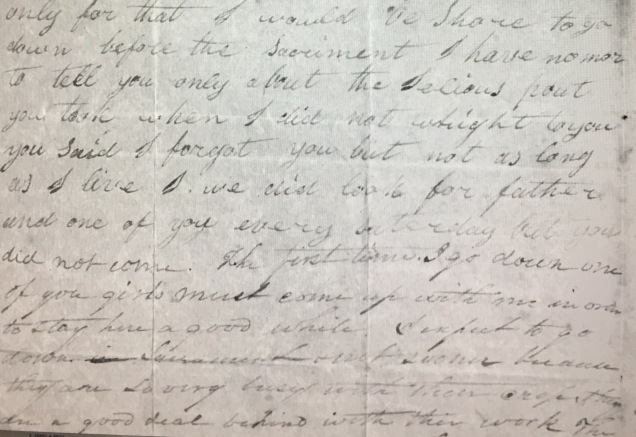

In the middle of the 1850s, tragedy strikes the McKenzie family with the suffering of Barbara McKenzie. Daniel reveals in a December 1854 letter to his uncle that his mother Barbara appears to be afflicted with a cancer of the mouth from which she is finding no relief. Daniel has been working as a physician and has been treating his mother’s illness since July when the sore in her mouth and glands in her neck began to enlarge. At first he used available treatments for a non-cancerous ulcer but fears he may have made the malignancy worse. He has had several other physicians look at the growth, and they concur that it is what was called at that time a Gelatinform cancer. Daniel writes, “The sore in her mouth continues to enlarge it now covers nearly all the roof of her mouth affecting the glands of her neck on the right side.”

During Barbara’s horrific illness Daniel says that Miss Barbara Stewart, daughter of Allan Stewart, has been staying with his mother. Barbara Stewart, has been living with the family of her brother-in-law by the surname Davis. She has also been working at the Seminary School founded by Rev. A. R. Graves. However, at this point she has left Barbara’s side. John, the youngest McKenzie son, regularly sits with his mother, and Daniel says he will stay with his mother for a while. The community has been plagued with “scarlatina” and the mumps. His brother Kenneth has contracted the mumps, and has had to stay away from the house for fear his mother might contract them. By April of 1855 Barbara was forced to give up her struggle. Reverend A. R. Graves preached her funeral service. More than likely she was buried on the family property near her husband and infant daughter in Covington County.

Apparently, Daniel begins his work as a physician in 1853 at Augusta, MS, according to his brother Hugh. As for the success of his work as a physician, Daniel says that his net profits for 1854 would not “amount to but little more than a cipher. I have not collected and am in debt for board and expense.” Daniel ends his letter with a comparison of the medicine and politics. He has found that he no longer supports the Whigs or the Democrats but is finding himself in line with the Know Nothing Party. He says in medicine and politics, “there has been and is yet many vague theories.” He also ads that if one enshrouds anything with mystery and secrecy it draws the attention of the curious, who must then, “see analyze and understand.” With that he says he really knows nothing about the new Know Nothing party but advocates most of the published principles. In simple terms he is probably leaning towards that party while still considering his political stance.

In 1856 Kenneth writes that Daniel is living in Raleigh, Smith County, MS. Daniel had married eighteen-year-old Sarah M. Blackwell of Smith County, MS in 1857. Their son John Duncan was born there on June 2, 1858. Mary “Mollie” Isabelle was born on February 29, 1860 in Raleigh in Smith County. According to the 1860 census, Allen Mckenzie, Daniel’s brother, was living in their household and working as a saddler. Since about May of 1853 Daniel had been practicing medicine. He is working in 1860 as a physician with real estate valued at one thousand two hundred dollars and a personal estate of seven thousand two hundred sixty-five dollars. Apparently, Daniel purchased property from his father-in-law, John G. Blackwell, who is a successful Smith County farmer. Before 1860, Daniel has persuaded his brothers to sell their parents’ Covington County property in order to purchase in Smith County. According to their correspondence, they are living on property along the Leaf River: “I have bargained for a track of land in this County 480 acres which is considered the best in the Co. for which I am to give $1000 … I want them to sell in Cov and pay the $1000 and take this.” It is possible that the land in Smith had not yet been entered in their names, for these McKenzie brothers are not listed in Boyd’s Family Maps of Smith County, Mississippi. However, their fathers-in-law are listed as owning Smith County property in 1860: John Blackwell and R.C. Duckworth.

John G. Blackwell (1819-1890) and Mary Thornton (1820-1892) were Sarah’s parents. According to Smith County, MS and Its Families, “John was a merchant and before the War between the States owned a vast amount of land.” In 1858, Daniel’s brother Duncan describes a trip to New Orleans with John Blackwell, likely on a merchandising trip. The two decided to drive a one-horse buggy to Brookhaven in order to save money by only boarding one horse while they took the train to New Orleans. Blackwell’s horse foundered early in the trip, so they substituted with one of Duncan’s horses. All went as planned until about fifteen miles from home:

he (Duncan’s horse) did well untill we got within about 15 miles

of home on our return when the wheel

Struck a Stump the axle tree broke

the horse scared ran with broken Buggy

a short distance when the Buggy turned

over hurting my side verry much so it has

not entirely got well yet tho not serious

like I thot it was — Duncan C. McKenzie

During the few years before the Civil War begins, Duncan McKenzie becomes the primary farmer on the Smith County property. Hugh is working as a merchant in a store on the property. Kenneth is working as a carpenter and Allen as a saddler. John, now married to Susan Duckworth is farming with his father-in-law. Daniel and his wife have their own property. Daniel is working as a physician when he decides to give up medicine for merchandising with John G. Blackwell. In November of 1858 he writes:

My health has been very bad since about the middle

of Sept. I had an attack of Typhoid Dysentery from

which I recovered very slowly. I was able to ride about

the first of this month. I rode several nights successively

a good distance. I now have Bronchitis in spite of my

efforts and those of another physician. The inflammation

was not arrested in its acute stage it is assuming

a chronic form, which I dread very much — Daniel C. McKenzie

Daniel continues to speak of his family:

My wife and child are well, my child, John Duncan,

is five months old remarkably large of his age,

Since I came to this place my professional ambition

has been fully gratified. When able I have had generally

about as much to do as I could. Collections have been

slow. I have determined to quit even if I fully regain

my health. I am engaged in merchandizing with

my father-in-law, John G. Blackwell …

If my life is spared and I gain sufficient health to attend

to anything I shall devote my time to this business. you may

see me next summer perhaps we will be getting our goods in N. York.

… If I am spared I will write again. — Daniel C. McKenzie

Unfortunately, he cannot be spared. Daniel dies in 1860 of typhoid fever on July 13 at home. He is buried in the older portion of the Raleigh Cemetery. According to his brothers Dunk and Kenneth, he was ill for nineteen days and was aware of his condition until the last three days. He told them he was probably going to die unless he rested easy on the 17th and 18th days of his illness. Dunk describes his death as follows:

On the morning of the day before he

died aparently not conscious of what

he was doing or Saying he wished to

be raised up in the bed, and Sarah

his wife told him he was geting beter

his answer was I am going home to serve

my Savior, and reached out his hand

to her, after he was laid back on the bed

he was conscious no more — Duncan C. McKenzie

According to MS Cemetery and Bible Records Volume XIII: A Publication of the Mississippi Genealogical Society, Daniel’s headstone can be found at Raleigh, MS Cemetery: Sacred to the Memory of Dr. D. C. McKenzie/ b. Richmond County, N. C./Aug. 9, 1823/ d. July 12, 1860.

Daniel’s Children

Daniel’s Aunt Effy McLaurin, his mother’s favorite sister, died about a year after Daniel. In her will she acknowledges all of Barbara’s living children and Daniel’s two children, John Duncan and “Mollie” Isabelle. A direct descendant of Daniel said that her mother and brother, Daniel’s great grandchildren, visited Smith County and found Daniel’s grave, his headstone broken by time and wear. Daniel’s grandchild, Mittie McKenzie Geeslin, who lived to be 101 years old, had the marker replaced with the exact wording as the original. Sarah M Blackwell died on August 25, 1884, in Mississippi, when she was forty-four years old, having never remarried. Sarah is buried with her parents and several siblings in Forest County, MS. Her great granddaughter replaced Sarah’s gravestone.

Daniel’s daughter, Mary “Mollie” Isabelle McKenzie, married Samuel H. Woody. On June 12, 1936 in Travis County, Texas, at the age of seventy-six Mary “Mollie” Isabelle died. The 1930 census names her as a patient in the Austin State Hospital. According to her death certificate, her residence was in Mills County, city of Goldthwaite. She is buried in North Brown Cemetery, Mills County, Texas. Never having children of her own, Mollie raised Helen, Orbal, and Willie P., her three stepchildren. Helen’s mother was Sam’s first wife Lelia. Lelia’s sister Elizabeth, Sam’s second wife, was the mother of Orbal and Willie. According to the 1900 Federal Census, Samuel H. Woody worked as a merchant in Goldthwaite. The photo of Mollie McKenzie and her “Aunt Lizzie” Elizabeth Blackwell, five years older, was originally submitted to Ancestry by a direct descendant.

John Duncan, Daniel’s son, was born on 2 June 1858 and married Mildred Parshanie “Shanie” Risher in 1886. Her parents were Hezekiah S. Risher and Mary Elizabeth Duckworth Richer. Mildred had eighteen half siblings. In 1900 the Federal Census shows John Duncan working as a dentist in Mills County, Texas, though he also farmed. He died on March 28, 1931 in Goldthwaite, Texas at the age of 72 and is buried there. His son Hugh was born in March of 1892, his daughter Mollie was born in May 1894, and his daughter Mittie was born in October 1898. According to the 1910 Federal Census, he also had a son Anse (known as Dutch) born about 1901, a son Ben born about 1904, a daughter Elsie born about 1904, Allen and Allie are listed as having just been born in 1910. Five of John Duncan’s children died in childhood: daughters Una and Sarah and sons J.D. and Allen.

According to a direct descendant, John Duncan and Mary “Molly” Isabelle left Smith County, MS for Texas probably after their mother’s passing in 1884. One of the family stories is that “Auntie Woody” came to Texas by train via New Orleans and attended the 1884 New Orleans, LA Cotton Exposition. She had a ring made from a gold piece at the Exposition which is still in the family’s possession. It is also likely that John Duncan and “Auntie Woody” made this trip together.

Sarah and her Blackwell family would have to take the credit for raising John Duncan and Mollie. Daniel and Sarah would have taken great pride in the adult lives of their children. Daniel would have taken particular pride in his granddaughter, Mittie McKenzie Geeslin. She taught in a one-room schoolhouse before her marriage and sought to further her education through lifelong reading.

Naming Daniel C. McKenzie

Duncan and Barbara McLaurin McKenzie, first generation Americans, attempted to follow the rules of Scottish naming. Their first daughter Catharine is named after her maternal grandmother, first son Kenneth is named after his paternal grandfather, second son Hugh is named after his maternal grandfather. According to the rules, the third son should have been named after the father or the father’s father’s father. However, his parents seem to have taken the opportunity of Daniel’s birth to make an homage to his second great Uncle Dr. Donald (Daniel) C. Stewart. Donald and Daniel are used interchangeably. Also, Daniel may not have been the third son. According to her husband, Barbara had eleven pregnancies. We can account for only eight, so there could have been an intervening child, who died very young.

Daniel is first mentioned in the Duncan McLaurin Papers in April of 1827 when he was about five years old. Donald (or Daniel) C. Stewart (d. 1830) of Greensboro, Guilford County, NC writes to his nephew and Daniel’s grandfather, Kenneth McKenzie (abt. 1768 – abt. 1834). Stewart offers his belated sympathy on the death of Kenneth’s wife. According to The Greensboro Patriot newspaper of this time period, Donald Stewart is an influential supporter of the Greensboro Academy. In this letter he also mentions Daniel:

I am glad to hear that my little

namesake is so healthy, and grows so well

I requested Mr. McLaurin (Duncan) to bring him up

the next trip he makes to this county;

if the little fellow should possess a capa=

=city, or turn for it, I will educate him — Donald C. Stewart

Unfortunately, Daniel never benefits from his second great uncle’s offer to pay for his education. According to The Greensboro Patriot of Wednesday, January 6, 1830, Dr. Donald Stewart dies “Wednesday last at 7 o’clock P.M.” Kenneth mentions “Dr. Donald Stewart” in his 1832 Power of Attorney when he leaves Richmond County, NC. During the probate hearing of Dr. Stewart’s will, it becomes clear that his extensive property has been exhausted in paying off creditors. Kenneth had hoped to inherit a portion of this property. Some believed at the time that the administrator of the estate since Stewart’s death had mismanaged and sold off some of the property to his own advantage. This, however, is never proved.

If Daniel inherits his second great uncle’s name in its entirety, it may be possible to discover what the middle initial C represents. The problem is that even in the Duncan McLaurin Correspondence, not many use their middle names in signatures, though they may use middle initials. Donald Stewart’s middle initial does not appear in a letter written to him by a relative, Dugald Stewart, from Ballachulish, Argyllshire in 1825. This letter is referenced on page 275 of Sketches of North Carolina by Rev. W. H. Foote. It describes the Battle of Guilford Courthouse in the American Revolution. Captain Dugald Stewart participated in this conflict with the 71st Frazier’s Highlanders under Lord Cornwallis.

Since Daniel’s middle initial likely derived from the Stewart family, it might not have stood for Calhoun. Calhoun may have been his younger brother Duncan C. McKenzie’s middle name, though that too is speculation. A few years after Daniel’s death, his brother John writes from the battlefield at Vicksburg to his Uncle Duncan that he has named his firstborn after Daniel, “I would be glad to see Susan and my little boy Daniel we named him after Brother give him his full name.” Since John dies in the Civil War, the C in his son’s name may have eventually come to stand for “Cooper,” a Duckworth family name. It would be gratifying to find the entire name listed in a family Bible.

Special thanks are here given to Paula Harvey for her generous contribution to this post.

Sources

Boyd, Gregory A., J.D. Family Maps of Smith County, Mississippi. Arphax Publishing Co.: Norman, Oklahoma. www.arphax.com. 2010.

Foote, Rev. William Henry. Sketches of North Carolina Historical and Biographical Illustrative of the Principles of a Portion of Her Early Settlers. Robert Carter: New York. 275.

Harvey, Paula. Photograph of Sarah Blackwell. Photograph of Sarah Blackwell and Mary “Mollie” Isabel McKenzie. Photograph of John Duncan McKenzie. Family Stories. via ancestry.com and email. 2016 – 2018.

Letters from Daniel C. McKenzie to his Uncle Duncan McLaurin. 3 July 1843, August 1847, 11 November 1851, 8 December 1854, 25 November 1858. Boxes 1 & 2. Duncan McLaurin Papers. David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Duke University.

Letters from Duncan C. McKenzie to his Uncle Duncan McLaurin. 11 July 1858, 21 July 1860. Boxes 1 & 2. Duncan McLaurin Papers. David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Duke University.

Letter from Duncan McKenzie to Duncan McLaurin. February 1844, March 1845, April 1845, July 1845, January 1846, June 1846. Boxes 1 & 2. Duncan McLaurin Papers. David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Duke University.

Letter from John McKenzie to Duncan McLaurin. 13 July 1862. Boxes 1 & 2. Duncan McLaurin Papers. David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Duke University.

Mississippi Genealogical Society. Mississippi Cemetery & Bible Records. University of Virginia. 1954.

Original data: Texas Department of State Health Services. Texas Death Certificates, 1903-1982. Austin, Texas. USA. ancestry.com. Texas, Death Certificates, 1903-1982 [database on-line]. Provo, Ut, USA: ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2013.

Smith County, Mississippi and its Families 1833-2003. Compiled and published by Smith County Genealogical Society, P.O. Box 356, Raleigh, Mississippi 39153. 2003. 77.

Wade, Nicholas. Before the Dawn: Recovering the Lost History of Our Ancestors. The Penguin Press: New York. 2006. 18.

Year: 1850; Census Place: Covington, Mississippi; Roll: M432_371; Page: 309B; Image: 207. https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv=1&db=1850usfedcenancestry&h=3391938

Year: 1860; Census Place: Smith, Mississippi; Roll: M653_591; Page: 353; Family History Library Film: 803591. https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv=1&db=1860usfedcenancestry&h=38861910

Year: 1900; Census Place: Goldthwaite, Mills, Texas; Page: 5; Enumeration District: 0111; FHL microfilm: 1241659. https;//search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv=1&db=1900usfedcen&h=54391200