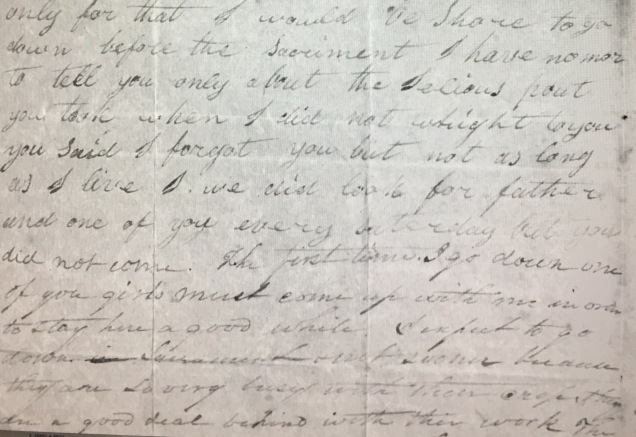

On June 16, 1817 Barbara McLaurin McKenzie wrote a letter to her favorite sister Effy because she was homesick for her family and “uneasy” about the health of her aging mother. Barbara was married to Duncan McKenzie, who farmed on the Peedee River within about sixty miles of Gum Swamp. Likely this was more than a couple of day’s travel in a wagon – less by horseback – yet still far enough away to impose an obstacle for very frequent visits. Barbara’s anxiety is palpable in these lines,

“Duncan came last night I was verry glad for we did not here a word Since uncle was down there I was very uneasy about Mother that she would be Sick this Summer I hope she will get well now my patience was a most out till Duncan came I kept dreaming every Knight of father and Mother and the all of you.”

The Duncan to whom she refers is probably her brother Duncan McLaurin. Barbara goes on to say in the letter that they are late with the crop and will not go down “till the Sacriment will be at the Hill” when she will stay a week. With the hopeful prospect of one or more of her sisters returning to PeeDee River with her to visit a while, she remarks on the “Jelious pout” her sister Effy displayed when Barbara did not write her: “you Said I forgot you but not as long as I live & we did look for father and one of you every Saturday but you did not come.” This last was to be prophetic for Barbara, especially after she migrated with her husband and children to Mississippi. Sisters and brothers still did not come, and her life would become so busy and probably sometimes so grueling that she would want to write but either never did or her letters may not have survived in this collection.

A physical complaint Barbara expressed in this letter would also appear in letters written by her husband and children many years later from Mississippi. She had developed a pain in her hip which she blamed on a rough wagon trip, “I had a mity sore pain in my hip for … too weeks I did go one night to preaching we rid very fast I was thinking it was that rased the pain.” This pain would follow her the rest of her life, a challenging one for most yeoman farmer women. For example, the family had no chimney in their new home in Mississippi and would have to bake their own bricks, which was not necessarily a priority – the crops were. Though it helped that they moved onto already cleared land, no chimney likely meant cooking outdoors and moving heavy pots.

According to later letters, the family had brought at least one enslaved woman with them from North Carolina, and possibly this was so that she could help Barbara when she was not needed to help in the fields. In 1839 Barbara would lose a second daughter to what was probably influenza, a year-old infant. Barbara would, of course, have been in charge of watching the children too young to work on the farm, among her many other tasks. Relationships between owners and the enslaved people on farms were often complicated. Barbara apparently particularly cared very much for one enslaved mother and her young daughter. However, it is difficult to gauge the reciprocity of affection in a relationship based on inequality and injustice, though individuals made their own choices in dealing with their own situations. Even while aging, Barbara’s son Kenneth attests to his mother’s ability to remain active even as he describes her as a “dried stick.” Widowed with six grown sons in 1847, Barbara’s life would end in 1855 after a horrific battle with mouth cancer. She would never know her grandchildren, for none of her sons married until after her death.

Nevertheless, Barbara McLaurin, my second great grandmother, must have had a fine early 19th century childhood. Probably born about five years before the turn of the 18th to 19th century, she likely spent a great deal of her time helping out on the family farm and enjoying the home that her father built when he purchased land near Gum Swamp at Laurel Hill, North Carolina. Born into the Hugh McLaurin and Catharine Calhoun McLaurin family, Barbara grew up enjoying a household filled with people and female companionship. Her many sisters by far outnumbered the two brothers, Duncan and John. By 1817 she and three of her older sisters were married: Jennett McLaurin (John) McCall, Sarah McLaurin (Duncan) Douglass, and Isabella McLaurin (Charles) Patterson. Three of her sisters would remain spinsters: Catharine, Mary, and Effy. Although Duncan never married, her brother John married Effie Stalker McLaurin.

Hugh McLaurin would likely not have concerned himself so much with educating daughters as with sons. Duncan, though only about four when he crossed the Atlantic, was by far the most literate of the children. His brother John was a literate farmer but less the man of intellectual curiosity – an infant when the family left Ballachulish in Argyll, Scotland for Wilmington, NC in 1790. According to Marguerite Whitfield, Hugh may have worked in the slate quarry at Ballachulish, Scotland, for he came to America with finances enough to cross the ocean with his family and to purchase property upon his arrival in the new land. The same need for readily available fertile land, affordably taxed, on which to establish a family farm must have been one motivating force that drove the Hugh McLaurin family from Scotland following family and friends that had gone before.

They came to a new continent from Scotland for many of the same reasons the Duncan McKenzie family was inspired to leave North Carolina for Mississippi. Owning land in the early nineteenth century was still considered essential for survival and even more necessary for living a prosperous life with at least a minimum ability to influence the outside forces that governed that life. This would change by the end of the century.

Hugh named his new home and farm Ballachulish, after his hometown in Argyll, Scotland. Duncan often spells the name of the farm “Ballacholish” and others spell it inconsistently in the Duncan McLaurin collection. In fact many Argyll families settled in North Carolina – McLaurins, McCalls, Stewarts, Calhouns and others – most of them becoming land and slaveholders. Many of them are buried in the old Stewartsville cemetery near Laurel Hill that survives today. All of Hugh McLaurin’s children are buried at Stewartsville except Barbara and her South Carolina sister Sarah Douglas. Barbara’s oldest daughter, Catherine McKenzie rests there, probably near her McKenzie grandmother, though no headstone remains. The remaining portion of Hugh McLaurin’s property, upon which his first home was built would pass from generation to generation. Upon Duncan McLaurin’s death in December of 1872, nephew Hugh McCall would inherit the property. This included the house built in 1865 by Duncan. According to the record of Marguerite Whitfield, a McCall descendant, the property was still in the hands of the McCall family in 1977. A later descendant of the McCalls has photographs and remembers the house still standing in 1982.

From Ballachulish to Mississippi, Barbara’s words speak to a strong family relationship that spans the distance of frontier roads and dreams of a better life.

Sources:

Bridges, Myrtle N. Estate Records 1772-1933 Richmond County North Carolina: Hardy – Meekins Book II. photocopy from the Brandon, MS Genealogy Room. “John McLaurin – 1864,” “Effy McLaurin – 1861,” and “Duncan McLaurin – 1872.”

Letter from Barbara McKenzie to Effy McLaurin. 16 June 1817. Duncan McLaurin Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Duke University.

Whitfield, Marguerite. Families of Ballachulish: McCalls, McLaurins And Related Families in Scotland County, North Carolina. The Pilot Press: Southern Pines, NC. 1978. (This text contains much valuable information, especially about the McCalls and about Scotland roots. However, the information on Barbara McLaurin McKenzie can be corrected with information from the Duncan McLaurin Papers and many other records. Also, two Effys are confused – Effy McLaurin, Barbara’s sister, and Effie Stalker McLaurin, John’s wife. Barbara’s sister Effy died in 1861, and listed Barbara’s children and grandchildren in her will. Effie Stalker McLaurin died in 1881 preceded in death by her husband and all of her children. Effie, John’s wife, is most likely the Effie that lived in her old age with the Hugh McCalls. Duncan McLaurin died in December of 1872, and his will was briefly probated within weeks of his death.)

Hi I just found your Blog, this is wonderful. I have been researching the Carolina McLaurins in Scotland for a long time. Have you seen the pre-1800 documents in the Collection, specifically those prior to when they emigrated in 1790? Cordially Hilton McLaurin

LikeLike

Thank you! I have been obsessed with this community of people for going on three years now. The only 18th century documents in the collection appear to be land transfers. I have transcribed most of the letters and some of the legal documents. The oldest information I have on the Hugh McLaurin family emigration is found in Marguerite L. Whitfield’s 1978 family history titled Families of Ballachulish: McCalls, McLaurins And Related Families. I hope to discover more in the international records at Salt Lake City in a few weeks.

LikeLike