On August 2, 1847, the first case of yellow fever in Mobile, Alabama was reported for that year. The disease, which did not originate in North America, was fairly common in United States port cities in the south during the 19th century. Outbreaks would usually begin in the summer and begin to decline after the first frost. Yellow fever’s early symptoms, similar to other fevers, made it difficult to diagnose. For this reason communities were slow to initiate warnings. Unaware of the true source of the disease, controversy ensued about whether sanitation or quarantine was the best response. The 1847 epidemic resulted in 78 deaths in the port city of Mobile, Alabama. It would be the turn of the 20th century in Cuba, where a U. S. Army Commission made the definitive discovery that the transmitter of yellow fever was the Aedes aegypti mosquito. Since the mosquito was the vector, quarantine would probably not have mattered much. Extra sanitation efforts might have made little difference in the spread of this disease except to ward off secondary infection. The mosquito vector breeds in fresh water. According to the author of “The Saffron Scourge: A History of Yellow Fever in Louisiana,” epidemic yellow fever in the United States was essentially eliminated after 1905 thanks to medical science and public health practices. The following is a brief but revealing encounter with one of its victims.

We first learn of “Stepmother” McKenzie in 1833 when Kenneth McKenzie proudly introduces his new son, Kenneth Pridgen McKenzie. He is writing to his son John when he breaks the news from Brunswick County, NC:

John and Betsy you have a little Brother born on the

7th October named Kenneth P for Pridgen I am

in my 65 year his mother in her 48th He was fully

as large as your Mary when born

I will call her Stepmother since her first name is never revealed in any of the Duncan McLaurin Papers, and that is how the letters reference her. She is forty-eight when her last child is born. In February 1840 Duncan McKenzie writes, “I heard from Stepmother in Dec she expects to move to Mi in the spring.” Though I have never found evidence of Kenneth’s death, Stepmother is a widow in 1840, perhaps for the second time. Duncan appears to feel some concern about her wellbeing. Stepmother’s marriage to Kenneth McKenzie was not her first. Her first marriage produced at least four daughters that we know of. One of those daughters was widowed and also had a son.

Stepmother must have been desperate to find a sense of security by coming to Mississippi to be near Duncan and his family. Perhaps, as Duncan likely fears, Stepmother and her family will become dependent upon him. Still, he does not appear to discourage her from coming and probably feels some responsibility for the family. He expresses some concern for their welfare once he has confirmation that they are on their way. In April 1840 Duncan receives information that Stepmother was to leave Wilmington on March 4 by way of schooner or steamer to Charleston, SC. From there she would continue to Mobile, AL. He writes to Duncan McLaurin:

I have been looking for my

Step Mother from Wilmington, I received a letter

from her dated the 2nd of March Stating that she

was to leave there on the 4 of the same month in a

vessel bound for Charleston SC from which place

She would take passage to Mobile, Ala, She

had not reached the latter place on the 10th Inst

I am uneasy for her safety

Duncan could have rested more easily, as he would soon learn, for Stepmother was likely more adventurous and resourceful than he might have thought. In July of 1840, after the party of four had arrived in Covington County and were welcomed into Duncan and Barbara McKenzie’s home, we learn of her travels.

Stepmother initially set out from Wilmington on the fifth of March en route, via probably steamship or schooner, to Charleston, SC — a distance of around 159 nautical miles. At the beginning of her journey, she likely passed near her former home with Kenneth McKenzie at the mouth of the Cape Fear River. Before passing what is today called Oak Island, she might have spied the lighthouse near her former home at the mouth of the Cape Fear River. She might have said a nostalgic good-bye to the birthplace of her young son. Or she may not have had time to direct young Kenneth’s attention to this landmark, for the seabirds following the vessel along the shoreline may have been too much of a distraction for two young boys. Stepmother also traveled with her four daughters and a widowed daughter’s young son — quite a number of people headed toward Covington County, MS and Duncan’s modest home.

However, the party was delayed two months after reaching Charleston, SC. Evidently, Stepmother’s funds were running out sooner than expected. In Charleston she made the decision to send one of her daughters back to a son-in-law in Wilmington and a second daughter stayed in Charleston. No evidence exists in the correspondence as to how this young woman was to fend for herself there. Perhaps they had family or friends in that place. Duncan does not explain further.

After a two month’s delay, Stepmother’s party of five boarded a schooner, captained by one James Nichols, en route to New Orleans, Louisiana. The schooner was nineteen days struggling against uncooperative winds in reaching port. During the nineteen day voyage traversing about 1,173 nautical miles, one daughter began a courtship with Captain Nichols, and in September of 1840 Duncan writes, “…their connubial knot was tied (on the 31st of May) in New Orleans, she thus took on her self the weals and woes of a sailors wife, her mother has not heard from her since.” Though Captain Nichols and the daughter headed for New York, they promised to return to Mississippi by way of Wilmington, where the Captain would give up command of the ship to the owners. By the end of 1840, Stepmother had received letters from her other two daughters left behind, with some assurance of their safety, but the fate of Captain Nichols and his wife is unknown.

Before leaving, Captain James Nichols placed Stepmother’s party of four (two widows and two sons) aboard a steamboat headed for Mobile, Alabama, where they arrived with seven dollars left. Duncan found land passage for them from Mobile to Covington County, MS through a friend, Peter McCallum. They stayed with Duncan and Barbara until they found a vacant house “in the neighborhood.” It appears that Duncan does not hear much from Stepmother while she lives amongst them. In one letter he describes them: “I think they are smart women,” and later says, “Stepmother and her daughter are verry industrious to make a living, they are not ashamed to ask for their wants and you know that is the first part of getting a thing.”

The following is Duncan’s account of Stepmother’s adventure:

you stated that Neil McLaurin of wilmington

had told you something about my Step Mothers leaving

that place in Febry or March, She left there on the 5th of March

and came as far as Charleston S C where She

was detained 2 months waiting a passage to Mobile

and for want of a sufficiency of funds she sent one

of her daughters back to Wilmington to a sone in laws

and left an other daughter in charles ton, She set

sail for New Orleans with her oldest daughter who

is a widdow & and an other daughter, her little sone, and her

widdowd daughters sone, five in number, owing

to contrary winds the Schooner was 19 days in making

the voyage during which time the captain was agree

=ably entertaind in courting the old ladys daughter

who he Married in New Orleans on the 31st May

leaving the two widdows to work through life

the best they could, James Nichols is the name

of the man, he parted with his mother in law

after seeing them on board a Steam boat bound

for Mobile with a promise of coming on

to her in Mi — After going a trip to New York

and returning to Wilmington where he would

surrender the schooner to the owners, and come

on with his wife, the two widdows arrived safe

in Mobile with 7$ left — P. McCallum to whom

I had previously written procured a passage for

them from thence to this place where they

arrived on last Saturday week, Still

in with us, but they are going to a vacant house

in the neighborhood, thus ends the narrative of the poor

widdows & their sones, If they are industrious they may

get along, I will try to see to this adopted little

brother he is a likely child —

In fact, Duncan did not have to put himself out for the young half brother, for his half sister, named Mrs. Turner, soon married the Yankee schoolteacher that Duncan thought brought the younger students on so well in their schooling. Reese H. Jones was from Pennsylvania, perhaps Philadelphia, for he returns home around 1846 to recover from stubborn mouth sores. While Jones is in Philadelphia, Stepmother and her daughter, their two sons — probably young teens by 1846 —leave Covington County for Mobile, Alabama. Stepmother and her family had been in Mississippi about six years when Duncan writes in January 1846, “Stepmother & crew left this for Mobile some time in Nov last Kenneth and all & if it suits their convenience they may stay there, her sone in law Reese H Jones came to Williams Burgh the day after she crew & caravan passd on their way to Mobile he of course followed they reached their place of destination and I hope that is the last of them.”

The last line seems to me a bit foreboding because it actually was the last of Stepmother. About nine months after Duncan McKenzie died in 1847, his oldest son Kenneth writes to his Uncle Duncan McLaurin of Stepmother: “I have to write … of Mobile grand … is no more she died of the yellow fever in Septr last Kenneth is in Mobile if he was separate from his sister I would try to tighten his reigns and put him to work.”

One is left only to imagine Stepmother’s suffering from yellow fever. Likely they were in temporary quarters when the disease struck. At first she might have suspected the fever and chills not unlike those she may have had before. The first five days would have brought nausea, vomiting, constipation, headache, and muscle pain in the legs and back. The acute stage would follow with the yellowing of the skin through jaundice. Hemorrhaging from almost any part of the body is common. Black vomit can occur as a result of blood from stomach hemorrhages being acted upon by stomach acids. This would take the form of almost involuntary vomiting. Before death, convulsions or coma occurred. If one recovered, and some did, it would begin about two weeks from the onset of the illness.

The treatment Stepmother was likely to have endured included heavy doses of Calomel, a mercury-based compound that purged the system. Other purging methods would have included blood-letting. These purging treatments are said to have had some limited success in treating the illness.

There is some evidence that soldiers returning from the Mexican War via New Orleans and Mobile may have made the epidemics worse during 1847. Many, many soldiers died of yellow fever while in Mexico. The ships and steamboats bringing them back through these ports perhaps harbored the deadly mosquito.

It is possible that Stepmother lies buried in the Old Church Street Cemetery in Mobile. The cemetery was originally set aside for yellow fever victims in 1819. During the epidemic of 1820, 274 people died, so the cemetery was put to immediate use. The cemetery covers over four acres.

Volume One of the Mobile County Burial Records from 1820-1865, page 113 lists “MaKenzie, Mrs., 60, North Carolina, Sept. 30, 1847.” The same record on page 112 lists, “Jones, R. H., 35, U. S., March 2, 1847.” Apparently Jones, likely weakened from his previous illness, succumbed first. His cause of death may also have been Yellow Fever. Whether Stepmother’s daughter, her son, and young Kenneth P. McKenzie survived the epidemic and perhaps made their home in Mobile is awaiting discovery.

Stepmother died in September of 1847. Ironically, in 1848 the American physician Joseph Clark Nott became one of the first to introduce the idea of the mosquito vector. It would take a second American war at the end of the 19th century in a tropical climate — Cuba during the Spanish-American War — to confirm the mosquito as the source of yellow fever.

SOURCES

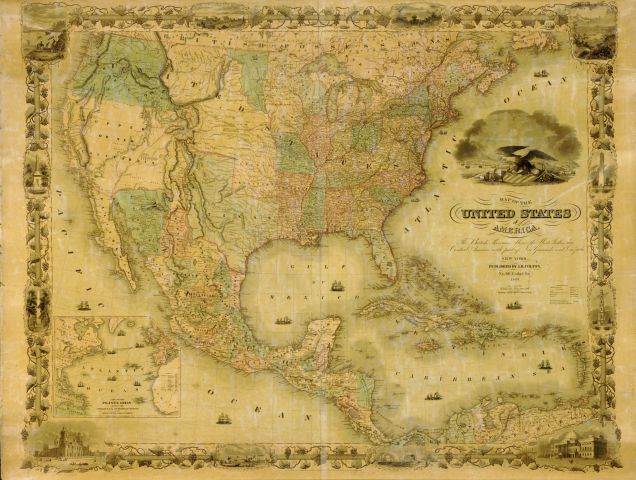

Colton, G. Woolworth, J. H. Colton, John M. Atwood, and William S. Barnard. Map of the US of America, the British Provinces, Mexico, the West Indies and Central America, with part of New Granada and Venezuela. New York: J. H. Colton, 1849. map. https://www.loc.gov/item/2007626897/.

“Distances Between United States Ports.” U.S. Department of Commerce. Dr. Rebecca M. Blank. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Jane Lubchenco, Ph.D. National Ocean Service. David M. Kennedy. 2012. p 4. https://nauticalcharts.noaa.gov/publications/docs/distances.pdf

Letter from Kenneth McKenzie to his son John McKenzie. 3 November 1833. Boxes 1 and 2. Duncan McLaurin Papers. David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Duke University.

Letter from Duncan McKenzie to Duncan McLaurin. 19 February 1840. Boxes 1 and 2. The Duncan McLaurin Papers. David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Duke University.

Letter from Duncan McKenzie to Duncan McLaurin. 26 April 1840. Boxes 1 and 2. The Duncan McLaurin Papers. David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Duke University.

Letter from Duncan McKenzie to Duncan McLaurin. 4 July 1840. Boxes 1 and 2. The Duncan McLaurin Papers. David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Duke University.

Letter from Duncan McKenzie to Duncan McLaurin. 26 September 1840. Boxes 1 and 2. The Duncan McLaurin Papers. David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Duke University.

Letter from Duncan McKenzie to Duncan McLaurin. 24 December 1840. Boxes 1 and 2. The Duncan McLaurin Papers. David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Duke University.

Letter from Duncan McKenzie to Duncan McLaurin. 22 March 1841. Boxes 1 and 2. The Duncan McLaurin Papers. David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Duke University.

Letter from Duncan McKenzie to Duncan McLaurin. January 1846. Boxes 1 and 2. The Duncan McLaurin Papers. David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Duke University.

Letter from Kenneth McKenzie to his Uncle Duncan McLaurin. 16 December 1847. Boxes 1 and 2. The Duncan McLaurin papers. David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Duke University.

Mitchell, Mrs. Lois Dumas and Mrs. Dorothy Ivison Moffett. Burial Records: Mobile County, Alabama 1820-1856, Vol. 1. Mobile Genealogical Society: Mobile, AL. 1863.

“The Saffron Scourge: a History of Yellow Fever in Louisiana, 1796-1905.” Jo Ann Carrigan. 1961. LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 666. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/666

“A Short History of Yellow Fever in the US.” Outbreak News Today. Accessed 24 June 2018. http://outbreaknewstoday.com/a-short-history-of-yellow-fever-in-the-us-89760/

Sledge, John S. “Church Street Graveyard.” Encyclopedia of Alabama. Accessed 28 June 2018. http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1039.

Yellow Fever. History Timeline Transcript Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Office of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services. Accessed 25 July 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/travel-training/local/HistoryEpidemiologyandVaccination/HistoryTimelineTranscript.pdf

“Yellow Fever.” Alabama Epidemic History. Alabama Genealogy Trails. Accessed 23 June 2018. http://genealogytrails.com/ala/epidemics.html

Dear Ms. Lane: I am a descendant of Duncan McLaurin of Covington County, MS (1771-1848) via Daniel > Cornelius > George Cornlieus > Mary Dudley (my gr-mother). Hoping I might be able to discuss the letters in the Duke University collection penned by the MS Duncan McLaurin. Not sure if you can access my email address via WordPress. If not, please post a reply and we’ll figure out how to connect.

Ed Payne

Jackson, MS

LikeLiked by 2 people