1840s: Daniel C. McKenzie

Daniel C. McKenzie, son of Duncan and Barbara McLaurin McKenzie, would only live to be thirty-seven years old – dying of typhoid fever. At the time of his death he was living on property in Smith County, Mississippi and married to Sarah Blackwell. The couple were raising two small children, son John Duncan and newborn daughter Mollie Isabel (Woody). Daniel was farming and also serving as a local physician.

About seventeen years before his death, when Daniel is twenty in 1843, he writes a letter to his uncle/former teacher Duncan McLaurin. Although he writes at his uncle’s request, the news he is most eager to convey is his acquiring a position teaching. The literary allusions in the letter are evidence that he was also intending to impress his uncle. The same uncle is likely responsible for instilling in Daniel a thirst for knowledge, even as he was unable ever to afford a scholarly education at an institution.

Daniel is charged with teaching from twenty to twenty-five students of varying ages, probably in a one-room building. The parents of his students pay him “from a dollar and fifty cents per month.” However, students pay more to learn Latin – two dollars and fifty cents. Since the letter is directed from Mt. Carmel, we can imagine that his school is located near this place.

Teachers often boarded with members of the community in which they taught. In Daniel’s case he is boarding with a Revolutionary War veteran, “formerly of South Carolina.” His name is John Baskin whose family consists of an aging daughter and her orphaned grandson. Daniel describes Baskin’s home as the perfect boarding situation for him:

his family [Baskin’s] is small & quiet he has a library

of Books well calculated to improve the intellect of

the young he is well informed and fond of reading

I occasionally read for him at night as he cannot read

by candlelight his eyes being dimed by a continually pass

ing stream of four score years and more the anecdotes

of this old gentleman are history to me they are interest

-ing and entertaining. — Daniel McKenzie

Perhaps it is Daniel’s exposure to this veteran of the Revolutionary War — “the anecdotes of this old gentleman are history to me” — that in 1846 inspires him to join a group of Covington County, MS young men, who volunteer to serve in the Mexican War.

Indeed, Daniel speaks of Baskin’s devotion to politics, describing his opinions as somewhere between John C. Calhoun and Thomas Jefferson – both proponents of states rights and territorial expansion. However, Jefferson’s vision of territorial expansion, opening the west for diversified and self-sufficient small farms, differed from the reality of the growing monoculture of cotton on large farms requiring slave labor that Calhoun defended. States rights and territorial expansion of slavery are important issues during the decade of the 1840s. Daniel, however, couches the description of Baskin’s politics with literary allusions as follows:

he is cherished

in principle like Paul at the feet of Gamalial

the contrasted feet of Calhoun & Jefferson this stripe

in his political garment he says is truly republican

but in reality it seems to me to be of rather a different

cast more like the gown of the old woman

Otway if you will allow me to make such comparisons — Daniel McKenzie

Gamalial is a historic Jewish teacher who is also lauded as a Christian saint. Somehow Gamalial bridges the gap between those two faiths.

As for the “old woman Otway,” Thomas Otway is a seventeenth century dramatist who believes the beautiful woman is a catalyst for war. Perhaps Baskin is looking into the future and speculating on the possibility of war over state’s rights and westward expansion. After all, even Andrew Jackson knew in his heart that nullification would come up again, and the next time he was sure the issue would have at its center the controversy over slavery. In the following quotation, Otway recounts the times in classical literature that women have been at the source of war. Classical history and literature was a significant part of 19th century education, and Daniel likely sought to impress his uncle with classical allusions.

What mighty ills have not been done by woman!

Who was’t betray’d the Capitol? A woman;

Who lost Mark Antony the world? A woman;

Who was the cause of a long ten years’ war,

And laid at last old Troy in ashes? Woman;

Destructive, damnable, deceitful woman! — Thomas Otway

Daniel expresses his wish to continue his education, but he is also aware that he is older now and must be out in the world making his way. Family members in other letters describe Daniel as the smallest of the six McKenzie brothers, and all of them competed in the fields to see who could pick the most cotton. Though Daniel picks the least of all, he does waver between teaching, studying to be a physician, and farming during the years before he marries.

The Mexican War

While the 25th Congress of the United States (1837-1839) debated what to do with the growing number of petitions to end slavery in the District of Columbia, the question of annexing Texas was a related issue prompting 54 petitions. As a result, the annexation of the Republic of Texas early in 1845 at the beginning of President Polk’s administration would inevitably fan the hot coals of the issue of slavery. Any new territory added to the United States was fraught with the political implications of unbalancing the power held by the southern states as a result of the 3/5 rule. This rule allowed more rural states, populated with fewer white male voters, to count enslaved persons as 3/5 of a person when calculating representation in Congress. In the decades before the Civil War, though enslaved people were by the 3/5 rule represented in Congress, they were not allowed the right to vote, nor could they petition Congress as women could. By the 1830s, with the influx of migrants and the rise in the slave population, the southern states had experienced a distinct political advantage when the issue of slavery arose. This advantage was threatened in the 1840s by the growing population of European immigrants to northern free states. Significantly, many of the citizens of the Republic of Texas in 1845 were farmers who had migrated from the southern states. Many from Mississippi had fled with their slaves to Texas during economic hard times.

Neither Duncan McKenzie, Daniel’s father, nor Duncan Calhoun, his cousin (see “The Duncan Calhoun Story” in this blog), expressed certainty that the annexation, and certainly not a war with Mexico over the territory, was a wise idea. McKenzie’s concern is war. He considers it somewhat cowardly that a compromise was reached with mightier Britain over the Oregon territory at the same time war with much weaker Mexico is stoked by the Polk administration. Duncan Calhoun’s concern, from his front row seat in Sabine Parish, Louisiana, is that the United States will not be able to “manage” and govern the acquisition of additional territory. Both stances were probably less common in Mississippi and Louisiana. The Democratic Party dominated in the South; McKenzie was a southern Whig. The Democratic party, dominant in Mississippi, was overwhelmingly for territorial expansion, support of slavery, and war with Mexico. In contrast to the South, northern Whigs would have shunned the expansion of slavery that might increase slave state representation. Initially, support for the Mexican War would come from mostly western states, both North and South. Illinois sent a large number of volunteers to the war. Whig congressmen would eventually agree to support the troops, even if they did not think war was necessary.

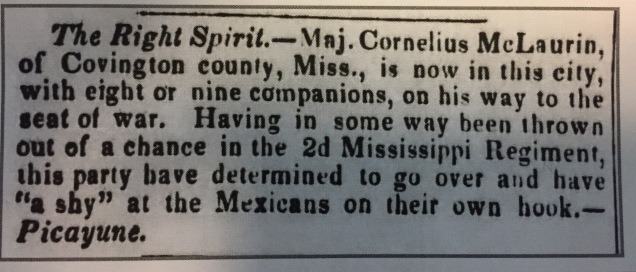

Duncan McKenzie was alive when his son Daniel set off for the Mexican War. In fact he appears quite insulted that the “Covington County Boys,” in the beginning part of the group of volunteers known as the Fencibles, were told to go back home when they presented themselves for military service. In June of 1846 he writes to Duncan McLaurin regarding the Mexican War:

The Mexican difficulties are quite familiar to us here There are more volunteers

than are wanting, the other day a company called the State fencibles tenderd

themselves to the governor for a permit to go and join genl Taylor the govr

asked them if they could not find anything to do at home —

query was not the governs question mortifying to the sensibility of the patriotic

Fencibles, in fact Govr Brown

absolutely refused raising any troops except by the express command of The President — Duncan McKenzie

This Covington County group included Daniel McKenzie and perhaps Kenneth, though Daniel is the only one who eventually stays with the group long enough to serve. Friend Cornelius McLaurin is also among the group.

Later in the same 1846 letter, Duncan McKenzie further clarifies his position in response to the prospect of President Polk avoiding war “on the Texas and Oregon questions.” Duncan responds by asking how any confidence can be placed in the “dmd clique, they profess one thing and do another.” Here Duncan comes out clearly against the annexation of Texas and the war that now looms:

The annexation

of Texas to this Union was positively inconsistent with the laws of honor

and secondly our claim on oregon to the 49th line of No Latitude is a presump

-tion unparalleled in the history of free government — Duncan McKenzie

In another few lines Duncan alludes to the spilling of American blood for such territorial aspirations and the ability of populist candidates to lead otherwise rational-thinking people around by the nose:

and watch ye our repub

-lic cannot wash out the stain only by much blood and how can we

wash from our desecrated hands that blood of innocence, it may be argued

that such was the will of the majority no no the majority would do right if

left to their own sober reflections, but when inflamed by wicked aspirants

they may err, at this moment all our earthly interests are in jeopardy — Duncan McKenzie

After the Republic of Texas was annexed in 1845, Mexico responded by cutting off diplomatic relations with the United States. President Polk sent John Slidell from Louisiana to negotiate the contested border with the Mexicans; President Herrera of Mexico refused to see Slidell. To further instigate the situation, Polk sent US troops under Zachary Taylor, who eventually moved his men into disputed border territory. Manifest destiny being the philosophy of the powerful southern members of Congress, it agreed with Polk’s call for war after Taylor’s troops were fired upon by Mexicans defending themselves against American incursions into what they considered their territory.

Support for the war across the country was quite high in the outset, though it waned as the war progressed. Daniel McKenzie, among other Covington County young men, was not alone in Mississippi in his fervor to volunteer. President Polk designated which states would send militia troops and how many from each state. Mississippi was called to send only one regiment of 1000 volunteer militia. According to author Sam Olden in “Mississippi and the U.S.-Mexican War, 1846-1848,” the response was so great in the state that “an estimated 17,000 boys were in Vicksburg wanting to enlist.” Many were sent home, including the Fencibles.

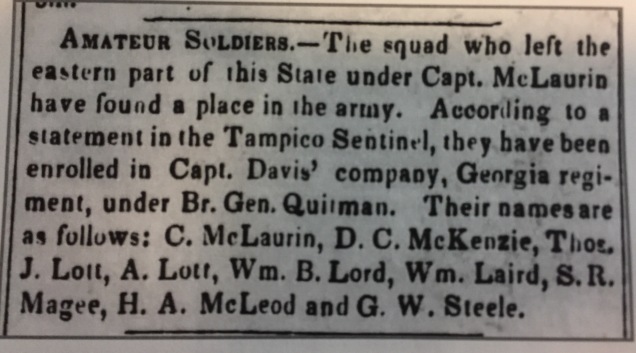

The Fencibles had begun by gathering men for their company from Covington and surrounding counties – thirty from Copiah County, according to Kenneth McKenzie. Governor Brown ordered them to march to Jackson without an officer. In Jackson, MS the group elected Ben C. Buckly Captain. Evidently, an argument then arose as to First Lieutenant’s place. As Kenneth explains, “but by fraud we were choised out, we revolted and broke the company.” Characteristically erring in judgement on the side of paranoia, Kenneth claims that Governor Brown was partial to the others when he sent the Covington boys home. Truth be told, they probably simply had filled their quota of volunteers. Kenneth goes on to say that the Covington boys raised several thousand dollars to pay their own expenses as volunteers. When they finally went to war, it was as unofficial volunteers or “amateur soldiers.”

Cornelius McLaurin’s Account

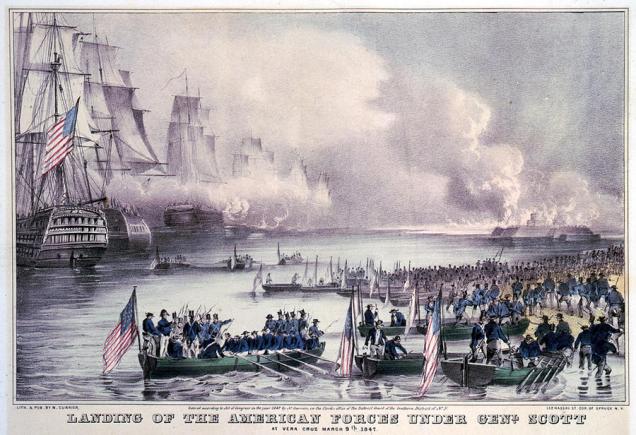

Another story complements most of Kenneth’s explanation. Over a decade later in 1860 General Cornelius McLaurin, who had been a member of the Covington County boys and with the group in Mexico, writes a letter in reply to J.F.H. Claiborne. Though not an actual participant in the Battle of Vera Cruz, McLaurin’s story corroborates others. Claiborne was a Congressman from Mississippi in the 24th and 25th Congress, but was likely working as a journalist and historian by 1860. Evidently, Claiborne had found information about the Covington County volunteers among the papers of General Quitman, under whom the Covington group served, and solicits McLaurin’s explanation. Cornelius McLaurin writes that, after being rejected, the company of nine left in January of 1847 financing their own adventure. In New Orleans they outfitted themselves with privates uniforms and weapons, medicines and directions for use, and left by sea for Tampico. At Tampico they attached themselves to Company D of the Georgia regiment under Quitman’s command. On the 7th or 8th of March Quitman’s forces left for Vera Cruz and the castle San Juan D’Ulloa. Once on land they slept the first night with their arms and the second day began to move inland. When the regiment encountered fire from a large party of Mexicans, Cornelius McLaurin was in camp sick with a fever. Illness was a major cause of death, especially among the volunteers.

The “Covington County Boys” as they would come to be known, were part of a contingent that engaged with Mexican soldiers at Vera Cruz. The skirmish lasted about thirty minutes. Quitman’s soldiers were the victors, though the siege would continue for some days. Among the six or eight wounded was one Thomas J. Lott of Covington County, wounded in the thigh. According to Cornelius McLaurin’s account, the wound appeared to be stable and improving until the injured were required to be moved to another location. Lott’s wound became infected and he soon died. Cornelius McLaurin recovered but adds in his account that seventeen lives were lost at Vera Cruz through injury — hundreds from illness. He claims they were all ill even after returning home. The little company, having left in January, did soon return home as hostilities appeared to Quitman to be winding down. Quitman found them passage on the America for a nineteen day trip to New Orleans. McLaurin also praises one Captain Irwin. It appears “Mr. McKenzie” from the group was sent to the Quartermaster to obtain items needed for Cornelius McLaurin’s recovery. Evidently, the regular Army was reluctant to answer the persistent requests from a volunteer, so Captain Irwin stepped in and told McKenzie that their needs were to be met without hesitation. According to McLaurin the Covington County boys included: Daniel C. McKenzie, George W. Steele, Arthur Lott, Wm. Laird, Wm Blair Lord, Laurin Rankin Magee, Hugh A. McLeod, Thomas J Lott, and Cornelius McLaurin.

Daniel C. McKenzie’s Account

In May of 1847 after he has had some time to absorb the death of his parent during his absence and recover from his experience in Mexico, Daniel writes to his uncle, Duncan McLaurin. In this letter he tells of receiving the news of his father’s death in a letter a few days before the company started for home. Once home, he found his family recovering from what he calls, “the epidemic typhus pneumonia which passed through the state in some places more violent than in others.” The family was surprised to see him since they had heard the company was headed toward the Mexican interior toward Jalapa (Xalapa). He claims to have “taken up my medical books again,” perhaps partly inspired by the illness that claimed so many in Mexico and the death of his fellow adventurer, Thomas Lott. Evidently, Daniel wrote to his uncle from Tampico, but either the letter never reached North Carolina or it did not survive in this collection. To explain their position as volunteers, Daniel says they were allowed even more access to the Quartermaster’s department than even privates in the regular Army:

Gen. Scott arrived there (at Tampico) on apple

-cation to whom we we’re permitted to enter any portion

of the volunteer army as amateurs for any length of

time we chose with the chance of drawing rations as

others with all the privileges of non commissioned

officers i.e. we could buy any thing in the Quarter Masters

department in the way of food which is not allowed privates

We paid our transportation received no pay did

no soldiers duties except fight when we saw the enemy

In my letters home I gave them the particulars of

my trials & c …

I was in but one fight while I staid in Mexico that at Vera Cruz and that a

skirmish, tho a pretty hard business I would call it

16 Georgians and 7 of us contended against 2 Regmnts of

the tawny creatures commanded by Gen Morales,, 11 of our

little number we’re hit 6 badly wounded Lott was all that died of his wound — Daniel McKenzie

It would seem that Captain Irwin’s orders were followed by the Quartermaster, but we can speculate that there might have been some prejudice against the volunteers on the part of the regular army soldiers, especially if the volunteers were required to do no extra duty. For the Covington County boys it must have been like one of those adventurous reality vacations gone awry when illness overtook them and a friend was lost to injury.

The “tawny creatures” comment is instructive regarding the attitude of slave holders to foreign people of color, disparaged on site for preconceived notions of the inferiority of their cultures and “creatures” suggesting a lesser form of human being. In Daniel’s defense, though, any person that is shooting at you, and you are required to shoot back at them might more easily be construed as a little less human. This appears true in any war. However, the idea that white entitlement may have played a role in the idea of manifest destiny, public support of war with Mexico, and in stoking this war with Mexico must be acknowledged in the light of Daniel’s comments and atrocities perpetrated on the Mexican people. According to a number of historians, including Daniel Walker Howe and Amy S. Greenberg, the undisciplined volunteers were responsible for reported atrocities against Mexican civilians as were some of the regular army, having learned brutality in the Indian Wars. Public opinion began to turn against the war as it lengthened. Embedded reporters kept the newspapers filled with battle accounts, casualty lists, and reports of atrocities perpetrated by Americans.

Though he does not describe the town of Vera Cruz, Daniel attempts to describe the Castle San Juan d’Ulloa or as he spells it San Juan de Cellos. It is an impressive fortress that extends into the sea. He compares the coral light house in size to one he saw at La Balize, Louisiana on the Mississippi River:

Castle San Juan de Cellos …

is situated more than a half mile in the sea

from the nearest point of the beach where ships of the largest

size can come and anchor by the walls so near that

you may step from one to the other. This castle, worthy of the

name too, covers ten acres of ground on water the wall in

the highest place is seventy feet being eight feet through at

the top and thirty where the sea water comes up to it. I should

judge 40 feet through at the base The wall is built of coral

stone the light house out of the same is as much larger

than the one at the Balize of the Miss River, which is a

large one, as the latter is larger than a camson brick

chimney on the walls of this castle were … 300 heavy

pieces of cannon which were kept warm from the morning

of the 10th to the 27th March tho they did but little damage — Daniel McKenzie

Daniel continues his account with information to which Cornelius McLaurin would know only from the accounts of others. He remarks on the illness, chronic dysentery, that plagued the little company of volunteers even after their return to Covington County. Admitting that his inclination was to return to the fray now that he was well, but he would not put his mother through that anxiety so soon after losing his father:

We went on to Alvarado a town 54 miles from Vera Cruz

on the coast which surrendered on our rear approach …

Gen Quitman took possession demolished some of their

forts spiked their cannon left a small garrison as however

Com Perry left a few small gunboats as a garrison. Quitman

with his portion of the army returned to Vera Cruz all of us that went

took sick we were almost unable to follow the army farther We

are at home. I am well but 4 of the others are not and I doubt their being

so soon their disease Chronic Dysentery …

My inclination would

lead me back. But while Mother lives I will not distress her by a similar

attempt. All are well Mamma in as good spirits as I could expect. — Daniel McKenzie

Daniel laments never actually seeing Mexican General Santa Anna and mentions a General Twiggs when accounting for their return from Alvarado. Though General Twiggs would be quite old at the outbreak of the Civil War, he still served in the Confederate Army, but his reputation was somewhat disparaged after he lost control of Ship Island on the Mississippi Sound early in the war. :

On our return from Alvarado Gen Twiggs was sent on toward

Jalapa with the advance of the army Gens Worth Patterson Shields

followed a few days afterwards. They got out to the mountain pass

called Cerro Gordon where they were met by Santa Anna

with a powerful Mexican force Genl Scott came up and on

the 17th and 18th April they fought. The American loss though heavy was

small compared to that of his adversary. — Daniel McKenzie

General Twiggs was among many soldiers who would gain useful battlefield and leadership experience in this war to serve them in the next conflagration, the looming Civil War. In fact General U. S. Grant, a veteran of Chapultepec, describes the Mexican War as, “one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation.”

Andrew Jackson Trussell’s Account

At the University of Texas at Arlington Library in Arlington, Texas the Trussell Collection, box 1, folder 3, contains letters of a young Lauderdale County Mississippian who enthusiastically volunteered against odds to serve in the Mexican War. Eight of Andrew Trussel’s letters are either partially or wholly transcribed and published by Douglas W. Richmond in a collection titled Essays on the Mexican War. The collection is edited by Richmond.

Upon reading Trussell’s correspondence from Buenavista, Mexico to his home in Mississippi, I was struck by two characteristics in his account that either corroborate an impression in Cornelius McLaurin’s letter or in Daniel McKenzie’s letter: prevalence of illness, especially among the volunteers; and apparent ill-will between the regular army and the volunteers.

In all three accounts illness is given as the major cause of death. Trussell writes in June of 1847 to his brother, “There are only 38 privates now in our company. When we left Vicksburg we numbered 90 men.” Earlier in the letter he writes, “We have, I believe, got clear of the desperate complaints of small pox. There were 22 of our company who had the small pox.” Later in a letter to a friend, he returns to the subject of illness, “We were first taken in New Orleans and while tossed to and fro on the mighty billows of the gulf for thirty-two days, many a brave and proud spirit found a watery grave.”

By October, though Trussell is still complaining to his brother about illness, he also mentions a conflict regarding a Lieutenant Amyx. It seems that some Mexicans killed two men during the night not far from their camp. This Lieutenant Amyx gathered ten or fifteen privates and, evidently without authorization, took off after them, traveling some eighteen miles away from the camp. Upon their return the next morning General Robert Wood had Amyx arrested. Apparently Trussell took issue with this arrest:

Wood had him arrested and the sentence of the court martial was read out on dress parade … he should be reduced from rank for three or four months and his pay stopped for the same time. Lieutenant Amyx is a good officer and a gentleman … He was tried by regular officers and they hate volunteers as they do the devil and there is no love lost, for the volunteers hate them. — Andrew Trussell

It is amazing to me that Trussell could not see how Amyx’s actions might be construed as gross insubordination. Was this a general problem with the volunteer soldiers? Perhaps, unused to military discipline, some misconstrued their mandate to engage the enemy when necessary. Contrary to Trussel’s anecdote, some reliable accounts describe the regular Army, undermanned at the time of war, as working well with the militia volunteers. The volunteers, it is said, were eager to follow the rules of the regular Army. In fact, Trussell himself requests that his brother try to get him an appointment to the regular Army.

Trussell spent his twelve months service in Mexico and returned safely home. Trussell writes specific descriptions that tell us a bit about life in the camps. He describes the food as mostly salt pork and beef, corn bread from the market and sometimes flour bread, milk and fresh pork. Pretty good eating for troops in a foreign land, I think. He says, “The only good thing we have here is the water. These are the best springs here that I have ever seen.” He also writes of the “fine churches in Saltillo.” Of the Mississippians he says, “But the Mississippians always wanted to fight when they are imposed on or mistreated.” He admits himself to stabbing a man in the shoulder, “but did not hurt him very bad. He is getting well and I was justifiable.” He also speaks of the “very lively and rich” Mexican girls and wonders if the girls back home will still look as pretty to him. However, he disparages the Mexicans in general and says they are not worthy of self-government, so he is against any attempt to make Mexico itself part of the United States.

According to Mexican War historian Amy Greenberg, author of A Wicked War: Polk, Clay, Lincoln, and the 1846 U.S. Invasion of Mexico, and others many of the atrocities committed against Mexicans during this war have been attributed to undisciplined U. S. volunteers.

Trussel is in Mexico for a year, the standard twelve month enlistment for a volunteer, though Daniel McKenzie and Cornelius McLaurin were barely there three months. It is interesting that in the year Trussell saw absolutely no enemy engagement, whereas the Covington County boys incurred injuries and one death from a skirmish.

_________________

The Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, signed in Mexico City on February 2, 1848, settled the war between Mexico and the United States. It stipulated that the two countries would peacefully negotiate future conflicts. The United States paid Mexico fifteen million dollars. The US also took over the debts previous Mexican governments owed American citizens. Mexico gave up claim to what became California and parts of what became New Mexico, Utah, Arizona, Nevada, Texas, Colorado, and Wyoming. The loss of this vast territory hurt Mexico. According to Daniel Walker Howe and other historians of this war, President James K. Polk’s goal in stoking war with Mexico was rooted in his desire for territory, especially California, for the United States. However, the immediate apparent justification of the war by the U.S. involved the U. S. aggression into disputed Texas southern border territory.

According to Jim Zeender, Senior Registrar in the National Archives Exhibits Office, if you find yourself in Pueblo, Colorado, you might visit the “Borderlands of Southern Colorado” exhibition at the El Pueblo AcMuseum there. On display you would find, contained in light-filtering acrylic, three pages — an original copy of the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo. You would see the signatures in iron gall ink of “American diplomat Nicholas Trist and Luis G. Cuevas, Bernardo Couto, and Miguel Atristain as plenipotentiary representatives of Mexico.

Daniel McKenzie did bring home one souvenir of his experience that was appreciated by all of his brothers. While in New Orleans, he purchased a new rifle, which Kenneth later refers to as Daniel’s “Spaniard gun.” Kenneth says that Allan killed “a fine buck” and “a few days ago he killed a turkey over 200 yards with the gun.” Daniel tells his Uncle Duncan to convey a message about the gun to his Uncle John McLaurin, “…tell Uncle John I bought a rifle in New Orleans and gave $45 dollars which will hold up — 300 yards I shot Mexicans at 100 yards distance with it — I will put it to better use and kill birds and squirrels.”

Sources

“Amateur Soldiers.” The Mississippi Free Trader. Natchez, MS 18 March 1847. 2. newspapers.com Accessed 20 May 2018.

“Covington County Military Resources; Mexican American War 1846-1848.” U.S. GenWeb Project. “General McLaurin to J. F. H. Claiborne; Jackson, Mississippi, July 16th, 1860.” http://msgw.org/covington/mexico.htm Accessed May 2016.

“From Tampico and the Island of Lobos.” The Weekly Mississippian. Jackson, MS. 19 March 1847. 2. newspapers.com Accessed 27 May 2018.

“Gen. Jefferson Davis.” The Natchez Weekly Courier. Natchez, MS. 25 August 1847. 1. newspapers.com Accessed 23 May 2018.

Howe, Daniel Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc. 2007. 731-743.

Letter from Kenneth McKenzie to Duncan McLaurin. may 1847. Boxes 1 and 2. Duncan McLaurin Papers. David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Duke University.

Letter from Daniel C. McKenzie to Duncan McLaurin. may 1847. Boxes 1 and 2. Duncan McLaurin papers. David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Duke University.

Letter from Kenneth McKenzie to Uncle Duncan McLaurin. 17 September 1847. Boxes 1 and 2. Duncan McLaurin papers. David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Duke University.

Magee, Rex B. “Covington Man Gave His for Mexico Years Ago.” Clarion Ledger. Jackson, MS. 20 March 1963. Published in Strickland, Jean and Patricia R. Edwards. Church Records of Covington County, MS: Presbyterian & Baptist. Moss Point, MS. 1988.

McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. The Oxford History of the United States. Volume VI. C. Vann Woodward, editor. Oxford University Press: New York. 1988. 4.

Miller, William Lee. Arguing About Slavery: The Great Battle in the United States Congress. Alfred A. Knopf: New York. 1996. 311.

Olden, Sam. “Mississippi and the U.S.-Mexican War, 1846-1848.” Mississippi History Now: An online publication of the Mississippi Historical Society. http://mshistorynow.mdah.state.ms.us/articles/202/mississippi-and-the-us-mexican-war-1846-1848 Accessed 26 May 2018.

“Our exchanges in this state …” The Mississippi Free Trader. Natchez, MS. 6 June 1846. 2 newspapers.com. Accessed 23 May 2018.

Richmond, Douglas W. “Andrew Trussell in Mexico: A Soldier’s Wartime Impressions, 1847-1848.” Essays on the Mexican War edited by Douglas W. Richmond. Texas A & M University Press: College Station Arlington, TX. 1986. 86, 87, 88, 91, 93, 94.

“The Right Spirit.” The Mississippi Free Trader. Natchez, MS. 19 January 1847. 2. newspapers.com Accessed 27 May 2018.

Zeender, Jim. “Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo is on the ‘Border’.” Posted by jessiekratz. 18 May 2018. https://prologue.blogs.archives.gov/2018/05/18/treaty-of-guadalupe-hidalgo-is-on-the-border/ Accessed 20 May 2018.

Greetings! We also are descendants of Kenneth McKenzie and have enjoyed your work immensely. We discovered the Duke Letters some time back and have worked for hours reading the letters and attempting to understand the time and place written. Your work fills so many gaps in meaning and perspective. Thanks! Mitch McKenzie, Austin Texas. Direct Descendant of John A. McKenzie captured in December 1864 at the battle of Nashville.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Amazing! Mitch, John had three sons according to my tree. From which are you descended?

LikeLike

My Father Is John David McKenzie II and his father John David I was son of Daniel McKenzie. My father was born in Grenada Mississippi in 1929 to his mother Velma Malone McKenzie. He had 9 siblings and at one time all 6 boys were serving in the military. We are gathering this week in Lockhart Texas for our annual reunion. We will be displaying your work there and have linked it to our reunion facebook page. Our research has found several McKenzie’s in North Ballichulish but have yet to find the ultimate Scottish line Kenneth descends, what have your works found? We just figured out his Mother is a Catherine Stewart McKenzie and haven’t had time to look deeper.

LikeLike

I am only a few days home from the Salt Lake City Library where I searched their international records for Catherine. I have found one unconfirmed lead. A Catherine Stewart and John McKenzie had a son Allan christened in 1786 in Lismore, Argyll, Scotland – From Scotland Births and Baptisms, 1564-1950. From the DMPs I know that Kenneth, born in 1768, had a brother named Donald and a youngest brother named Allan; and that Donald was working in the slate quarry at Ballachulish during the 1840s. That would make Kenneth about 18 years older than this Allan. Allan emigrated to Australia some time during the 1830s. I found a few leads on Allan McKenzie in Australia but nothing definite. If Kenneth is Catherine’s son, he was born in Scotland and came to the US after the American Revolution. I also scanned most of Banks McLaurin’s Quarterly that he published in the 1960s – 1980s. He delineates all of the McLaurins in the US and Canada and Barbara McLaurin’s family is family “F”. Enjoy the reunion. I will look for your connection on my tree. One of John’s descendants, Dave McKenzie, wrote a book called The Spirit’s Journey. He is descended from John Duncan McKenzie (1862-1950) and Ollie English (all three of John’s sons married at least twice). After the Civil War Susan Duckworth, wife of John (1833-1865) remarried a George Risher. They raised John’s three sons in Laurel, MS, where they are buried.

LikeLike

We are in contact with Dave McKenzie and he came to our reunion a couple years back in Red River Army Depot in Texarkana Texas. His son Mike McKenzie doe’s Radio in Birmingham Alabama. Good to get a date of birth for Kenneth, thank you. Also there is a letter about 1840-41 regarding Duncans Scottish Uncle where Duncan basically says don’t come to Mississippi as life is tough. I wonder if that is the Alan you mention, but I read somewhere that they settled in New Zealand about 1843 -45? It is easy to get the lines confused with so many Kenneth’s, John’s, Duncan’s, and Hugh’s all brothers. So you think 1790’s in Guilford near Donald Stewart? I have the land records from the Pee Dee River land in 1811. of course there is also Kenneth McKenzie the Revolutionary war guy who also settled on the Pee Dee to confuse things more. Exactly where do you fall on the tree?

LikeLike

Donald is the uncle with whom Duncan corresponded. Allen is the uncle who went to Australia. Kenneth wanted to inherit Donald Stewart’s property, but little was left of it according to Mendenhall. I am descended from Duncan’s son, Allen, my great grandfather. You appear to be descended from John and Susan Duckworth’s oldest son, Daniel McKenzie. Thank you for sharing my blog.

LikeLike