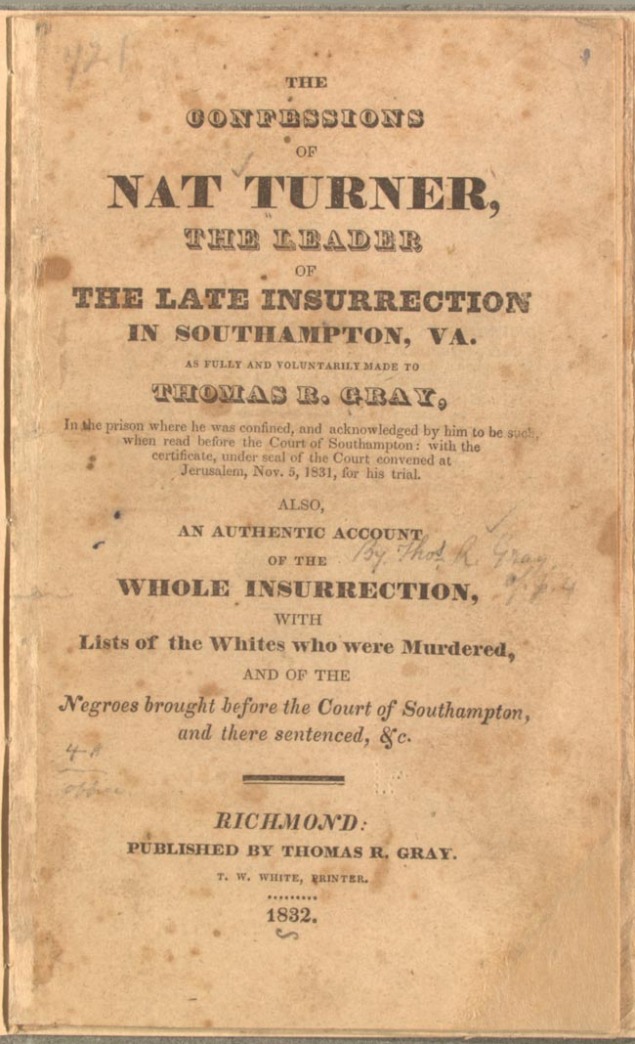

By mid-decade the slave states had begun to live under a growing pall of fear due to several slave insurrections. In 1822, Denmark Vesey, a carpenter and freed slave in South Carolina, is said to have plotted a slave insurrection along with others. The insurrection was uncovered before it could take place, when a slave told of the plan. Vesey and the others were convicted of the crime and executed. At around the same time, the controversy over slaves in the territories, resulting in the Missouri Compromise, was fresh in the minds of slaveholders, and the threat of insurrection served to make them more uneasy and fearful, especially if one lived in a state where enslaved people outnumbered free whites, as they did in Mississippi. In August of 1831 the Nat Turner Rebellion again sent ripples of fear throughout slaveholding states. Though the rebellious people were executed, suspicion of further plots caused militia’s in some slaveholding communities to begin policing. Slaveholding states also began passing laws restricting the movement, assembly, and education of enslaved people.

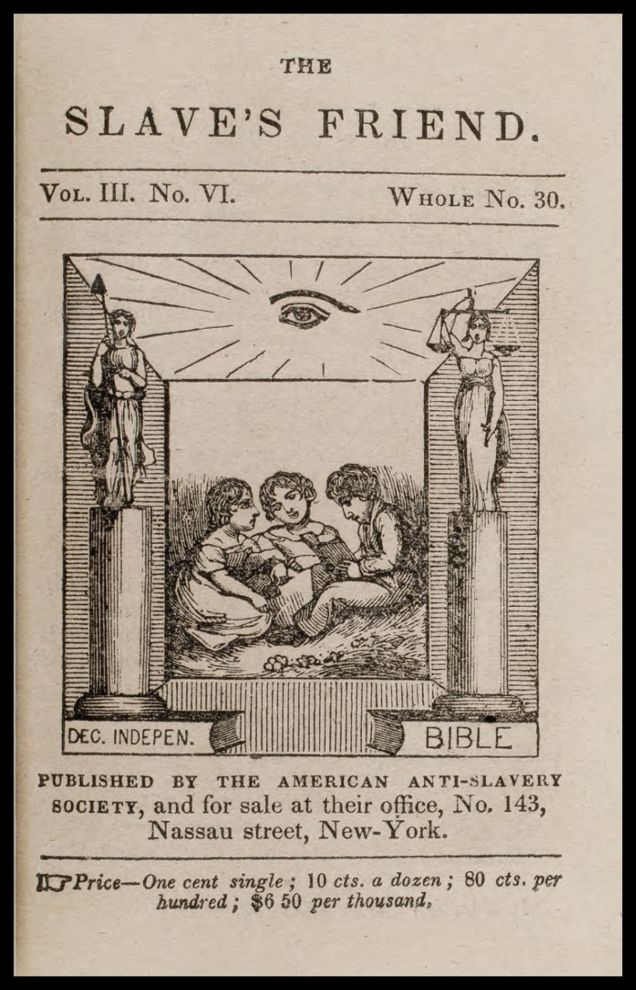

According to Arguing About Slavery by William Lee Miller, by 1833 the abolitionist movement had organized, marked by the founding of the American Anti-Slavery Society. William Loyd Garrison, John Greenleaf Whittier, and Theodore Weld were prominent supporters of this organization. The group was largely made up of pacifists, such as Quakers, and many women found an avenue for political influence through social causes such as the abolitionists movement. The organization’s headquarters was in New York City, Nassau Street, from which anti-slavery pamphlets were sent through the mail to all parts of the country. Slaveholding southerners read abolitionist material as no other group in the U.S. did with the exception of the abolitionists themselves. This fueled anger, and the term “Nassau Street” evoked threatening connotations. The abolitionist movement was a relatively small and decidedly religious group at first, incurring much displeasure and even violent reaction in the North as well as the South. The American Anti-Slavery Society held the philosophy that slavery should end immediately, and were bitterly opposed to another philosophy held by many who did not approve of slavery that enslaved people and free blacks should be relocated out of the country.

However, Mississippi was experiencing such profits from the growth of cotton that the fear of slave insurrection does not come across often in Duncan McKenzie’s letters of the 1830s. Duncan McKenzie himself had brought at least two enslaved people into Mississippi when he migrated from North Carolina. McKenzie’s brother-in-law/cousin John McLaurin wrote to his brother in November of 1832, confiding that Duncan McKenzie has attended the “fair” at Richmond County NC and purchased two people. McKenzie’s first notion was to purchase “Vilet”, also known as “Nicholson’s Girl” from Thomas Crawford. On second thought, he finally purchased an enslaved woman from John Morrison and another from John Fairley, all of this with McNeil’s note. In this manner two enslaved women would be leaving family, community, and relocating in Mississippi. Increasing references to slaves and slavery begin to appear in Duncan McKenzie’s letters by 1837. During the 1830s, the buying and selling of slaves in Mississippi was very profitable. By 1837 speculation in land and cotton in Mississippi was rampant and would soon lead to financial crisis in the state. For example, in April of 1837 Duncan McKenzie writes to Duncan McLaurin of three mutual acquaintances buying slaves on credit. He marvels at the risk they are taking and wonders how long it will take for them to pay off their debt.

“…Archd Anderson, Archd Wilkinson

and Lachlin McLaurin, Black bot each of them a Negro

man for which they are to give $1:650 each, query

how long will it take the boys to pay their prices at

the present rates of hiring which is $175 for Such

boys, allowing 10 percent per annum at compound

interest till paid”

Being much more cautious, McKenzie did not go out of his way to purchase labor he could not afford, though by 1840, according to tax records, he owned eight enslaved people. He further illuminates the speculation in slaves in a June 1837 letter to his brother-in-law.

“You said the National Intelligencer informed you that Negros

were selling in the west at 1/4 less than given last Spring or

fall, yes the Inteligencer may tell you that in many instances they

are sold at 1/4 the sum given or promised and the poor debtor left

3/4 of the sum to be raised from his other property if such be

is it to be feared that the evil will become common

What will become of Black Lachlin the carpenter who bot

a negro man for which he promised $1650 to be paid next Jan.

Many others are similarly situated”

By October of 1837 Duncan has purchased a person from LMcL, perhaps the same Black Lachlin he mentioned taking risks in speculating. Evidently LMcL purchased a “Negro woman & 2 children” for $600. He then sells them to Duncan McKenzie for $950. Duncan calls it “not a small shave.”

Speculating in the buying and selling of human beings seems cruel enough, but human property was passed from generation to generation in wills. Duncan McKenzie mentions in March of 1837 the dispersal of property by the father of another mutual acquaintance of his and Duncan McLaurin’s.

“… his father’s Estate was divided. Aunt drew the

old Negro woman & $156 also a bond in $1.000 for her

maintenance in case the property should die the

Negroes increased So that there was one for each heir

and two to divide among the whole, those were valued

and kept in the family”

We are generally stunned at reading the detached tone with which Duncan McKenzie writes of the buying and selling of human beings. He may as well have been talking about horses or cattle. Fathoming such inhumanity to man requires a look at the environment and philosophy slaveholders embraced in the nineteenth century. Especially for the recent Scottish immigrants, it was a decidedly European view based in colonialism. Many justified colonial pursuits by rooting them in the cause of spreading Christianity to pagan people. Where foreign cultures appeared more primitive and less technologically advanced, it was easy to justify “lording it over them,” especially if doing so was going to increase one’s own wealth and position. This is nothing new in our world past or present. It is called racism or caste and has no moral justification. By the Nineteenth Century, as industrialization took hold worldwide, a more enlightened view of slavery and the slave trade began to emerge. England led the world in ending its trans-Atlantic slave trade from Africa and abolishing slavery – albeit slavery was most prevalent in her colonies and reparations were paid to the slaveholders, so it was perhaps more easily accomplished. However, at the same time the emerging textile industry required more and more cotton to meet its market. This demanding crop had been once grown in manageable amounts on small farms before the age of colonialism, but the amounts needed for increased production in textile mills required an enormous labor force. On its face it must have seemed simply easier and perhaps more profitable to continue slavery than it was to convert to a system of paid labor, especially in the United States, where newly opened and fertile land suitable for growing labor intensive crops was increasing the demand for labor, if you could justify the immorality.

If enslaving another human being is immoral, and you are doing it, you have to find a philosophy to justify your behavior. An easy and common justification was that some human beings, by pseudo-scientific observation, were incapable of functioning on their own in more technologically advanced and “civilized” societies. Therefore, it was more humane and Christian to keep them productively employed than it was to set them free to be overwhelmed in the act of thinking and behaving on their own recognizance. At the same time, the fear of retribution from their own labor force was growing among slaveowners.The bottom line, however, is that a slaveholder might not as easily build a fortune so fast or so sure if a paid labor source were required. Surely, not every person who was forced to work in the fields would, if given the choice, choose to do so.

In addition, the newly-born republic of the United States of America, in the attempt to compromise with slaveholding, which went against the very basic idea of a republic, had installed the mechanism of the 3/5 rule to keep the slaveholding class politically powerful.

In November of 1836 the fear has not yet crept into his correspondence, but Duncan McKenzie finds himself refuting a claim by neighbors, some of whom were relatives and acquaintances of Duncan McLaurin, that his wife, Barbara, is in danger of exhaustion. Barbara is busy with her family of six boys, two of them young enough to be underfoot – too young to do much work in the fields. In addition, she was responsible for keeping watch over the enslaved children on the farm, who were too young to work. It is probable that her workload had increased as had everyone else’s in the move to Mississippi. However, she probably had some household help when someone could be spared from the crops. She is likely responsible for maintaining a garden, providing meals and clothing for everyone working on the place, and watching the small children. A thousand daily tasks had become routine to her and were expected by the rest of the family. Duncan McKenzie replies to his brother-in-law’s concerns, “It is true Barbra has a considerable charge on account of the children but Allan being the oldest takes considerable pains in conducting his little brother John and Jones and Niles (enslaved children) all are very attentive to Jbae Elly sones name he is as handsome a black child as I ever saw.” It would seem that on a small farm with so many daily interactions that the humanity of people would shine through, and eventually, the system would seem to break down. However, this does not seem to have happened.

Some servants were valued more than others in slaveholding families, though the elephant in the room within these relationships was that one party was there by coercion and not by his or her choice. In 1838 when Barbara delivers her daughter Mary Catharine, Elly is there to help Duncan deliver the child. Elly is the most often mentioned of the enslaved people working on the Duncan McKenzie farm, “ … till the morning of the 9th August at one a clock she (Barbara) was delivered of a daughter no one being in attendance but myself and Negro woman Elly, yet all was well and I dressed the little Stranger before anyone had time to come to our assistance.” In 1839 Barbara has been ill, but when illness struck, it potentially struck everyone working on the farm. At the same time Barbara is struck with the diahrrea, (in the 19th century often deadly) two other people on the farm: Barbara’s youngest son, John, and Elly’s youngest child. During the same year, Duncan sends his condolences to his brother-in-law for the “loss of the boy Moses,” an evidently valued servant. In another instance, Duncan McKenzie says, “Duncan McBryde is in a peck of trouble as it appears old Dorcas will be Sold to the best bidder and Duncan not able to buy her.” The circumstances of her sale are not clear, but she was clearly valued.

By 1839 Duncan emphasizes the economic prowess of cotton and slaves in Mississippi. “… I find that from the sinner to the Saint that the cotton plant engrosses the chief of the conversation, a few years passd the purchase of Negroes was the hobby but now it is paying for them and that must be done by cotton or by the sale of the Negroes and other stuff of the purchasers.”

I will conclude with a chilling story told by Duncan McKenzie in an 1839 letter to his brother-in-law, “… on last Tuesday week two little girls one 14 years old and the other younger were going to a quilting and were assaulted by a Negro man on the road.” The man caught the horse and removed the girl from it. She began screaming, a neighbor, who happened to own the Negro heard the commotion. He claimed to have seen the Negro attempting to rape the young girl. When he called out, the Negro ran. As a result fourteen white men hunted him down and hanged him. This is an example of what, in my opinion, is absolutely the greatest tragedy of slavery in the United States and the worst affront to a republican system of government, that enslaved people had no recourse to justice at all – no assurance that they were assumed innocent until proven guilty by a jury of their peers. They had absolutely no voice in their condition. Laws did exist in most slave states to protect the enslaved, but generally from the point of view that they were property and not to be abused. In a case like this, it is probable that the slaveowner was within his rights to permit the lynching of his property. Apparently, it occurred to no one (or did it?) that this man may have not intended to hurt the children at all but took advantage of an opportunity to steal a horse for his escape. Perhaps the man’s escaping to freedom was the greater and most feared crime in the minds of slaveholders. This instance manifests the repressive fear of uprising by enslaved people that was growing in Mississippi and across the slaveholding South.

Books on the Slave Trade

The following three texts summarized here, which may interest the reader of this account, address the international trans-Atlantic slave trade and the domestic slave trade in the United States. They also provide a window into the forces that placed women like Elly; young children Niles, Jones, and Jbae; or McLaurin’s servant Moses and McBryde’s Dorcas in bondage to Duncan McKenzie and others in Mississippi or Duncan McLaurin in North Carolina. We can also imagine how centuries of economic forces grew into a caste system in the United States that, despite our efforts, continues to lurk in the recesses of the minds of us all, unless we are individually able to expose it and dispel it in the healing light of day.

In THE LEDGER AND THE CHAIN, the author, Joshua Rothman, has mined the primary sources among other records related to the slave trading trio Isaac Franklin, John Armfield, and Rice Ballard, partners who built their domestic slave merchandizing enterprise from the early 1830s. Not only does Rothman profile these men, but he also profiles some of the people they trafficked, sometimes bound in coffles overland for hundreds of miles but mostly by way of coastal ships from the nation’s capitol and Virginia to Natchez, Mississippi and the Port of New Orleans. The three bought and sold enslaved human beings for profit, supported in this endeavor by American bankers, lawyers, and others in the merchandizing and legal system. They took advantage of the Fugitive Slave Law. While professing to kind treatment and to avoiding family separation, primary sources reveal an unrelenting movement from jail to jail and pen to pen against all odds including disease, state restrictions, and economic difficulties of the Jacksonian era. They allowed abusive handlers and participated in sexual abuse. In the end, it was the thriving domestic market for enslaved labor and their deft use of credit that drove them to greater financial success and acceptance into the upper echelons of American society. The glowing obituaries of these men do not mention the source of their wealth or the object of their business acumen. According to Rothman, this omission has perpetuated the “sanitized and racist” version of slavery and embedding of the caste system that has historically put the formerly enslaved at the bottom.

THE DILIGENT: A VOYAGE THROUGH THE WORLDS OF THE SLAVE TRADE by Robert Harms is based on the young French mariner First Lieutenant Robert Durand’s journal that he kept aboard THE DILIGENT, a grain ship refitted to carry slaves by the Billy brothers of Vannes, a town near the port of Nantes in France. This private slaving enterprise began in May of 1731 and ended in February of 1733, a tragedy for the two hundred and fifty-six Africans. Durand’s journal contained one hundred and thirteen pages of text and drawings made on the voyage from Nantes to the West African coast and back. The author was able to research and validate the information in the Durand’s journal to expand and create an account of this voyage, allowing us a nuanced insight into the variety of local interests and motivation for profit that characterize what we often refer to as a generic slave trade. The author humanizes and brings to life this one of around forty thousand voyages of the centuries long trade.

Greg Grandin’s THE EMPIRE OF NECESSITY: THE UNTOLD HISTORY OF A SLAVE REBELLION IN THE AGE OF LIBERTY recounts, from primary sources, tales of shipboard rebellions among the enslaved, defying their bondage. The early nineteenth century saw an “explosion” in the centuries old trans Atlantic slave trade, resulting from worldwide demand for labor-intensive products such as cotton and sugar upon which many made fortunes. Grandin both exposes and dispels the attitude upon which African enslavement rested that the enslaved were “loyal and simpleminded” with no “interior self” or will to take control of their own destiny. The irony is that this attitude was held during the West’s movement toward liberty and equality, which seemed to acknowledge and elevate a human being’s right to control his destiny. The author explores this theme by recounting the capture of the slaver NEPTUNE by the French pirate Mordeille and the fate of the captives in coastal Brazil and Uraguay. However, most of Grandin’s book is focused on the true account of New England’s Amasa Delano and his ill-fated encounter with the TRYAL. It explores the successful rebellion of the captives led by educated Muslim Africans, Babo and Mori, aboard the TRYAL, captained by the Spaniard Benito Cereno. Since Delano’s experience formed the basis of Herman Melville’s novel BENITO CERENO, Melville’s more existential attitude toward slavery is also addressed in Grandin’s text.

SOURCES

Miller, William Lee. Arguing About Slavery: The Great Battle in the United States Congress. Alfred A. Knopf: New York. 1996. 97.

Letter from Duncan McKenzie to Duncan McLaurin. March 1837. Boxes 1 & 2. Duncan McLaurin Papers. David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscripts Library. Duke University.

Letter from Duncan McKenzie to Duncan McLaurin. April 1837. Boxes 1 & 2. Duncan McLaurin Papers. David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscripts Library. Duke University.

Letter from Duncan McKenzie to Duncan McLaurin. June 1837. Boxes 1 & 2. Duncan McLaurin Papers. David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscripts Library. Duke University.

Letter from Duncan McKenzie to Duncan McLaurin. October 1837. Boxes 1 & 2. Duncan McLaurin Papers David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Duke University.

Letter from Duncan McKenzie to Duncan McLaurin. March 1838. Boxes 1 & 2. Duncan McLaurin Papers. David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Duke University.

Letter from Duncan McKenzie to Duncan McLaurin. November 1838. Boxes 1 & 2. Duncan McLaurin Papers. David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Duke University.

Letter from John McKenzie to Duncan McLaurin. November 1832. Box 1. Duncan McLaurin Papers. David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Duke University.

Excellent research and writing Thank You for posting!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike